Perhaps not surprising, these dueling cohorts fall neatly along political party lines. Each has logical arguments. The worriers point to higher infection rates and number of cases, the non-worriers to relatively low severity accompanying those cases. These attitudes manifest in policies for masking, school modality, and social gatherings, among others. I get both sides, but neither is perfect. There is a fine line between altruism and moral superiority, and a somewhat thicker line between apathy and brazen disregard for others. I’ve been on the COVID-caution spectrum from Day 1. My rationale has generally been about negative externalities. I don’t want COVID, to be sure, I am more stressed about spreading it to someone else. While this is certainly a possibility given Omicron’s penchant to sidestep the vaccine, I tend to veer off toward rather unrealistic scenarios. “What if I take my mask off for a second to drink of water during class, I get COVID, I give it to my dog, who licks the mailman, who then gets COVID and spreads it to his immunocompromised grandfather.” I have written about negative externalities before. Essentially, a choice made by person A negatively impacts person B, who had nothing to do with the decision. In this case, my choice impacts my mailman’s fictitious grandfather, which would definitely be a negative externality. However, this is improbable and bordering on impossible. One might even call it catastrophizing. If you’ve ever overthought a scenario to its most terrible and absurd conclusion, you have catastrophized. Catastrophizing distorts our perspective, creating a cognitive spiral towards the worst possible outcome. Amidst the grind that is COVID, it is no surprise that catastrophizing is related to anxiety and depression, but as hope crests the horizon, some people may be paralyzed by two years of playing out worst-case scenarios to embrace it. In the coming months, the messaging will likely recommend a letting down of our collective COVID guard. But the catastrophizing folks might need extra coaxing. One helpful mantra may be Zeynep’s Law. Named for Zeynep Tufekci, it states “Until there is substantial and repeated evidence otherwise, assume counterintuitive findings to be false, and second-order effects to be dwarfed by first-order ones in magnitude.” I’ve simplified it to “Don’t overweight what might happen for what will happen.” My mailman’s grandfather is probably not going to get COVID because of me, but my class will definitely be better if I don’t pass out from dehydration. The first-order effect of 40 students getting a better educational experience outweighs the slim-to-none second-order effect of my implausible COVID domino rally. This is normal. We tend to overweight low probabilities when the payoff is big (e.g., we all think we have a chance to win the lottery). The COVID payoff (i.e., another person’s life) is huge, and so caution here can—and has been—a useful risk mitigation strategy. As the death toll surpasses 900,000 in the United States, risk mitigation is still paramount, and there will always be a place in public health for caring about other people. There is also a place for sound judgment and rational choices.

0 Comments

Therein lies the problem with comparing academic credentials. In the US, we love the idea that anyone can do anything if they work hard enough. Bootstraps and the like. It’s a devastatingly beautiful myth perpetuated by tales of underdogs, overachievers, and Cinderella stories. Hard work is certainly correlated with achievement, but opportunities are not distributed equally. So when we inquire about someone’s education, what are we really asking about?

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives have become commonplace in most organizations, and while we can argue their effectiveness, as a culture we are at least acknowledging that the American workplace is often not diverse, equitable, or inclusive. One noble, if unfulfilled, aim of DEI trainings is to help companies make fair hiring decisions through implicit bias seminars, online modules, redacted information, and interview guidelines. The idea is to prevent discrimination based on things like age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, family stage, socioeconomic status, and disability. Each candidate’s body of work should, theoretically, speak for itself and create a fair comparison. However, in striving for an objective assessment, one traditional demographic variable escapes scrutiny and remains part of the discussion: education, be it degrees acquired, affiliated institutions, grade point average, or test scores. The problem is that, in many ways, one’s academic background serves as a proxy for those very factors. We don’t choose our race or gender, but we are not in full control of our academic outcomes either. So in trying to be diverse, equitable, and inclusive, why do we put so much weight on something that aggregates many baked-in biases and disparities? A few more examples. Question structure and order favors advantaged students. Even how a test is framed can influence the outcome by inducing stigma priming. For instance, Black students perform worse when a test is declared an assessment of ‘intellectual ability’ and female students perform worse when the goal of a math test is to uncover ‘gender differences’. In both cases, framing triggers stereotype threat and produces a self-fulfilling prophesy. Perhaps the starkest example is that Black students score lower on the SAT if asked to identify their race before the test than if asked afterward (See study 4). Because of historical discrimination and identity biases, the sheer reminder of race and gender shapes educational performance. A host of other predictors favor the privileged. Recent studies show that air pollution negatively effects cognitive functioning while green spaces provide ‘mental extensions that allow us to think well’. Not surprisingly, low income areas—urban or rural— have more air pollution and less green space than high income areas, creating a cumulative parallel between socioeconomic status and academic achievement. Perhaps the biggest challenge is that the shift in trajectory occurs so early in life. Your career depends on your college degree, which depends on your high school GPA, which depends on the quality of your middle school, which depends on your school district—all of which depends upon family wealth, social status, race, etc. The academic snowball starts rolling at a young age. Some predictors are less obvious. Have you ever ‘choked’ on an exam, in an interview, on an important presentation? Research shows the best way to overcome this phenomenon is by blending practice with experience to quell the natural nerves stemming from these situations. Now consider the disadvantage of a first-generation college student, or a second grader with a single working parent, or a high schooler working to help with family bills. How would these students gain the practice or experience to level the playing field with a fourth-generation college student, a second grader with two parents and private tutor, or a high schooler not chipping in for rent? The list goes on. Having children makes it harder to earn advanced degrees. Depression and anxiety can limit academic achievement. You would never ask a job candidate if they take antidepressants or how many children they have, but there is reason to expect differences in educational history based on these factors. This all makes sense. Perhaps that is why we have simultaneously witnessed a dramatic drop in undergraduate enrollment with an increase in graduate enrollment, or “the educational equivalent of the rich getting richer.” The relationship between demographic variables is nothing new, but given these relationships, how do we adjust our hiring practices in the workplace and advanced degree program placement? There is general agreement that screening by gender, race, and age is discriminatory, but filtering by education may not be that different. The last thing I want to do is denigrate the value of education or the merit of personal academic achievement. I chose this profession because I believe in the power of education and the promise it affords my students. But we can innovate policies to account for the noise. For instance, we could eliminate the GPA on entry-level job applications the same way many institutions phased out the SAT as a prerequisite for college. We could have implicit bias training to minimize discrimination based on whether a student went to an ivy league school, HBCU, community college, or state university. We could avoid stress triggers like money and food in our elementary math assessments. We could handicap standardized test scores based on access to clean air in the school district. We could do more for students with mental or physical disabilities than adding twenty minutes to their allotted exam time. We will never be able to compare academic apples to apples, but maybe that’s not the goal. After all, oranges grow in a different climate with different soil and different amounts of water—but they are no less delicious. I understand that job requirements are there for a reason. If you are unable to operate a forklift, you should not get the forklift operator position. I also understand the necessity for objective metrics of academic performance. This is not a participation trophy situation, but I do believe we need to be thoughtful in how we assess academic achievement across candidates. Graduate school programs and managers of entry-level positions are usually looking for potential, and screening out individuals based on a distorted number or school name precludes a lot of potential.

My wife calls this “meeting with no.” In essence, I’ve set my default to no, so turning to a yes requires effort. This is not trivial. Humans love to go with the default. Setting a default is one of the most consistent nudges employed to alter behavior. Research has shown the power of default in everything from organ donation to 401K sign-ups. However, what happens when the default option produces an undesirable behavior? My no paints a conversation in a negative light. My no creates an uphill battle just to get to neutral ground. If no is the first instinct, a yes is hard to achieve. But isn’t there something to be said for the first instinct? The common advice when you face a tough decision is to ‘go with your gut’. If you are taking a multiple-choice exam and can’t decide, trust your first instinct. Research, however, says otherwise. Just as I, upon deeper consideration, end up wanting to meet friends or go to the farmer’s market, our gut choice is not always the correct one. While some decisions benefit from intuition, others require deliberation. In four studies, Kruger, Wirtz and Miller (2005) found that students more often changed their answer from incorrect to correct than vice versa. They called this the first instinct fallacy, which is directly counter to what SAT and GRE prep courses had long lauded as the ideal strategy. Humans are programmed this way. Imagine you are back in high school, and the teacher hands you your graded test. You notice for one question, you erased the correct answer to put the wrong one. That feeling looms much larger in our memory than the handful of questions where you did the opposite. In fact, you may not even notice the answers you correctly changed. The point is that we trust our first response, which when can lead to faulty answers for complex problems. I argue that this fallacy applies to discussion of race in America. There is a moment in every TV or podcast interview, political or economic debate, or personal conversation about race where you can determine if a meaningful discussion will occur. It happens almost immediately after the subject is broached. The response could be non-verbal, like a frustrated sigh, a roll of the eyes, a dismissive laugh, a shake of the head. It could be spoken out loud, like “America isn’t racist,” or “We solved the issue of racism,” or “I don’t see color,” or “We are living in a post-racial world,” or more dismissively, “Oh not this again.” The person has met the conversation with no, hitting the shutoff valve that prevents the discussion from even starting. I get it. Remember, this is my jam. My first instinct is to say no to anything that disrupts my routine, makes me uncomfortable, wasn’t planned, or requires effort. A snap judgment is made by me (“We don’t need more kale”) before the idea (“Let’s have a morning walk at the Farmer’s Market instead of the bike path”) has even sunk in. It’s no wonder that discussions of race are met with no, particularly by white people. They are inherently uncomfortable, they disrupt the routine of white privilege, they force us to change our plans, they require effort. But this is a deliberative—not intuitive—cognitive process. At the risk of oversimplification, an open mind may be the essential ingredient to engage in a dialogue around race in America. If the gut response is to deny existence of the problem, the conversation never happens. The answer has been marked and won’t be changed. However, this is not a true/false test. This is not even a multiple-choice quiz. This is a working document, which will have erasures, strikethroughs, notes in the margins, post-its, corrections, highlights, and scribbles. As I’ve written about before, you don’t have to be a subject expert and we are going to make mistakes. The goal is not for white people to feel personal shame and responsibility for all of the injustices of human history. The goal is to engage in dialogue that leads to meaningful action, social change, equitable opportunity, and policy reform. While the premise is simple, I acknowledge that the execution is not. By opening the door to the conversation, we embrace discomfort and vulnerability, we expect to change our plans, we are open to disagreement with friends and interruption to our routines. But the right answer is not always the first one or the simple one. Occam’s razor does not apply to this context. Complex issues require complex dialogue. Having an open mind is key.

Value is difficult to define because it depends on context. Instrumental value is the value that something or someone can achieve or attain. It is derivative by nature, and can fluctuate based on the desirability of the outcome. The instrumental value of a can of beans, for instance, changes based on how hungry you are. Intrinsic value, on the other hand, is the inherent worth of something through its sheer existence. It does not fluctuate, nor does it need to achieve or attain anything to garner that value.

Instrumental value is how we apply the term in economics. The market dictates the cost of goods and services and we can exchange our money for something of equivalent value. A one-dollar bill may buy you that can of beans, but that requires us to extract instrumental value from that dollar. By itself, it is just a small piece of green paper. The can of beans, on the other hand, has more intrinsic value. It consists of caloric energy, sugars, carbohydrates, all of which are essential properties and require no exchange to be valuable. So what kind of value do we place on people in the US in 2021? I’d like to believe we value individuals intrinsically, that they don’t have to earn it. But that is not the reality. Instead our social institutions and cultural norms reflect our emphasis on instrumental value. We value what can be extracted from or earned by individuals. Some examples. Veterans would be treated better if we valued their service. Employers would raise wages—and consumers would fit the bill—if we valued labor. A college degree would not plunge you into debt if we valued education. The Affordable Care Act wouldn’t be continually under attack if we valued physical health. The elderly would not suffer disproportionate loneliness if we valued mental health. School shootings would not occur if we valued children over guns. Customers would wear a mask if we valued essential workers. Black people wouldn’t be incarcerated at a rate four times higher than white people if black lives mattered. The LGBTQ+ community would not be constantly battling in the Supreme Court if we valued civil rights. Wages would not be stagnant if we valued ‘hard work’. Childcare would be factored into our GDP if we valued families. The death penalty would not subsist if we valued the sanctity of life. Poverty would not exist if we valued human dignity. In each case (and there are many more), the institution is broken. The value is not placed on individuals, rather it is ascribed to the output they produce. We do not intrinsically value ‘hard work’, only the instrumental value we decide your type of work is worth. We will gripe when restaurant prices increase, but not mind that the person making our food needs a second job to afford rent. We thank veterans for their service and wish moms a Happy Mother’s Day, but our socioeconomic system values veterans and working mothers them less than, say, accountants and lawyers. Instrumental value is derived from a societal judgment about what matters, and I believe we have a value misalignment in our incentive structure. This is not an attack on capitalism, democracy, or meritocracy. It is an observation on the contradiction of our American rhetoric, leaving us two options to attain consistency. The first is easy: match the message to reality. Proceed with business as usual—but stop pretending we value each other intrinsically. Continue an economy where CEOs benefit from a pandemic while their employees suffer. Write more tax codes that give Jeff Bezos a $4,000 child tax credit. Treat job-seekers as ungrateful for wanting better wages. Create voting laws that disproportionately impact people of color. Ban teaching critical race theory in schools. If we choose this path, we simply need to change our words to match our actions. I am not encouraging this, but at least we will be consistent. The second option is much more challenging: match reality to the message. There are countless considerations: a universal basic income, climate change coalitions, free community college, minimum wage increases, reparations, a negative income tax, an ultra-millionaire tax, hazard pay for pandemic essential workers. But there are also ways to demonstrate we value people intrinsically without financial investment. We can change our mindset by making Juneteenth a Federal Holiday, applying Title IX protections to LGBTQ+ students, and not calling poverty a choice. It sounds pie-in-the-sky to think that reshaping our value system could fix our norms and institutions. These policies and programs are far from perfect. But humans are not perfect, so why would our solutions be? If, however, we strive to form a more perfect Union, we should ascribe value to people for who they are, not just for what they do. I’m pulling for option 2. The US vaccination goal has shifted from herd immunity to simply getting as many needles in arms as possible. But the underlying obstacle remains the same: how do you persuade people to get the shot?

In recent weeks, vaccine incentive programs have bubbled up all over the country, but few have garnered the attention of Governor DeWine’s “Vax-a-Million” lottery. Last Wednesday, Abbigail Bugenske (age 22) won the first of five million-dollar prizes and Joseph Costello (age 14) won a full-ride scholarship to college. While critics remain, the Associated Press analysis concluded the state vaccination rate is up 33% since the announcement. President Biden endorsed Ohio’s program last week, and other states have begun similar lotteries. Originally I was skeptical of the Vax-a-Million lottery. I argued to put $100 in the pocket of every newly vaccinated person because people usually prefer a sure thing over some chance of a larger payout. But Governor DeWine leveraged another aspect of prospect theory, namely that individuals tend to overweight low probabilities. That is why we buy insurance, go to casinos, and play the lottery to begin with. Governor DeWine simply applied this behavioral trait to his vaccination strategy. And, perhaps unwittingly, he employed an additional persuasion tactic—he generated ‘social proof’. Social proof, a term coined by Robert Cialdini, suggests that people alter their behavior to be more like people around them. Imagine it is your first day at a new job. You are in jeans and everyone else is wearing a suit. What will you wear tomorrow? Not only do humans have an innate desire to fit in with others, we are more receptive to suggestions if people similar to us have already engaged in that behavior. That is why we ask friends for Netflix recommendations and visit Tripadvisor before planning a vacation. We seek the advice of others because we think we will like what they like. Social proof is more effective when the desired behavior is observable. For instance, people are more likely to wash their hands when others are watching. This is one reason social proof was a useful persuasion tool with mask-wearing. Even people who didn’t ‘believe in’ masks wore them to not stand out from the group. But vaccines are invisible. Sure, you can get a sticker or button, but there is less social pressure to conform to the group because there is no visible proof that the group exists. The genius of the Vax-a-Million lottery is that it manufactured its own social proof by leveraging social media. Every article about the program has hundreds or thousands of comments pushing the dialogue toward vaccination. Not all are positive, but there is a chorus of “I got my shot and feel so relieved!” and “My whole family is fully vaccinated!” Giving space for these comments creates a public forum where people can observe the group mentality. It underscores that many people—your friends, neighbors, fellow Ohioans—are engaging in the same behavior to achieve a shared goal. How do we maintain this momentum and offer more social proof to those still on the vaccine fence? It could be as simple as changing the headline. Instead of highlighting the number of people who have not received the vaccine, focus on the percentage who has. With more people getting vaccinated every day, this group continues to expand, and the desire to be a part of it will too. [This piece was originally published in the Columbus Dispatch.]

Framing the Argument Our brains only have so much capacity, so how you frame the argument is critical. The following frames have been unsuccessful for the vaccine hesitant:

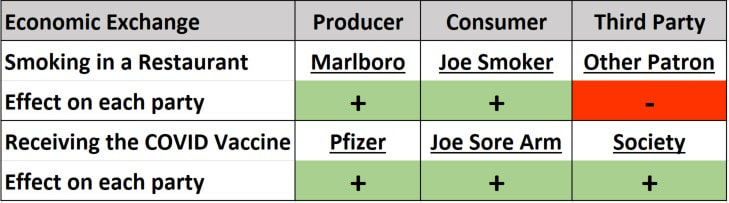

These frames failed for a variety of reasons. In many ways, we rebooted the problems we had with masks: indifference, defiance, skepticism, mistrust, misinformation, Trump-loyalty, and selfishness. Failure to achieve herd immunity will have long-lasting effects not just for those 30% but the global population. To prevent these negative externalities we need to bypass logic, emotions, and heartstrings, and frame the message around incentives. Positive & Negative Externalities A negative externality occurs when a third party incurs a cost due to some transaction between two other parties. Consider a person smoking a cigarette at the table next to you in a restaurant. Marlboro produced the product, Joe Smoker bought and consumed it, but you incur the cost of that exchange (secondhand smoke). The key is that Marlboro and the smoker chose to engage in the exchange and you did not, and while they receive net gains, you suffer a net loss—a negative externality. (Note: I have nothing against smoking; it was just the easiest example). With vaccines, the exchange produces positive externalities. Pfizer makes a vaccine, Joe Sore Arm receives it, and because that transaction mitigates the spread of COVID, society-at-large benefits. We are not part of Joe’s decision, but we benefit from it. Joe’s exchange is especially beneficial to those individuals (e.g., immuno-compromised) who are unable to complete their own exchange. Whereas the smoking example is a win-win-loss, vaccines represents a win-win-win. Overcoming Externalities

There are two ways to overcome externalities: penalize or incentivize the exchange that causes it. Policies are often put in place with the express purpose of reducing negative externalities. Smoking bans in restaurants reduce secondhand smoke; highway speed limits reduce fatal accidents. The problem is that policies created to reduce negative externalities are often framed as infringements on personal freedoms (e.g., the smoker gives up his right to smoke; the driver loses his freedom to drive fast). The aim of these policies is not to restrict individual liberty; the restriction is just the simplest means to an end. When no policy is in place to penalize negative externalities, individuals are not motivated to change their behavior. Heaps of evidence proved the effectiveness of masks, yet with no real punishment for not wearing one, many refused. Similarly, we cannot fine people for not getting the vaccine. Vaccine passports could be viewed as a penalty, but besides ethical issues, framing the argument this way only makes vaccine hesitant folks dig their heels in more. The other policy option is to use the carrot rather than the stick. Often, humans just need a nudge to alter their behavior in a way that leads to positive externalities. The government subsidizes the installation of solar panels. This represents a net gain for the homeowner, and because it lessens the strain on the power grid, a net gain for the entire community. Companies create wellness programs that reward healthy living. The employee benefits through better health, the company benefits through increased productivity, and society benefits by a net reduction in health insurance premiums. Cash Payments for Vaccine Hold-Outs All sorts of companies are offering incentives to induce vaccinations, but free donuts and hotdogs might just not be enough for the final 30%. Creating a COVID sweepstakes could work, but why not offer people cold hard cash to take the vaccine. A recent study finds that offering $100 would be effective. But who among the unvaccinated population would be nudged by cash incentives? Anti-vaxxers don’t get the measles vaccine so why would they get one for COVID? Conspiracy theorists think the vaccine causes infertility, so that’s another non-starter. Some people cannot or should not receive the shot for a variety of reasons (e.g., medical conditions). Skeptics don’t trust all the data in the world, so $100 probably won’t overcome that hurdle. That leaves us with what I call the Apathetics. Apathetics aren’t anti-vaccine, just indifferent. Perhaps they’ve already had COVID, the CVS is too far of a drive, they don’t like needles, they feel healthy enough, they just don’t feel like it. This is the target market that may be nudged by a $100 payout. Thirty-percent of Americans is roughly 100 million people. Of those, let’s say one-third (30 million) are Apathetics. Giving each of them a $100 bill with their shot means that, at a cost of 3 billion dollars, we could move our total vaccinated population from 70%-80%. Is it fair? Not really. Is it worth it? Yes. Every new infection is a chance for mutation, so when you consider the externalities, it’s a bargain. Three billion dollars to move the needle on herd immunity is a message frame I can get behind.

One network that often goes overlooked is our challenge network, a term coined by Adam Grant. Basically, while we all like people who give us praise and support, if we want to improve, we need someone to push back, someone to disagree with us. (There’s no “Try harder” button on Facebook). This seems intuitive. If you shoot foul shots at 50% and your coach says “Keep up the good work!” you may feel satisfied, but you may never improve. If you want to increase that percentage, you need critical feedback, like “Let’s break down your form and work on the follow-through.” This is initially harder to hear, but will help you in the long run. The coach challenged you.

Chances are you have a few of these people in your life already. The teacher who gives a full-page of red-inked comments, the personal trainer who makes you do a burnout, the friend who helps you kick a detrimental habit, your AA sponsor. A challenger is not exactly a motivator (e.g., “You can do anything you set your mind to!”), or a contrarian (“I wouldn’t do it that way.”), or a devil’s advocate (e.g., “Sure…but”), or even a mentor (“Here is what I would do.”). The challenger moves from vague platitudes to specific advice with the singular goal of making you better at something. Anyone who says “You may not like me now but you will thank me later” is challenging you. Grant outlines why we should create a challenge network in Think Again. I’m interested in how to do it. The first step is to identify candidates:

By now you probably thought of a few people who fit those criteria. How do you make them a part of your challenge network? This is where it gets tricky. Most people are conflict averse, meaning we avoid confrontation. Remember the whole point of this person is to challenge/confront you, essentially inviting conflict where it doesn’t need to be. We are also loss averse, meaning we’d rather not lose a friend than gain one. Asking someone to be brutally honest with you runs the risk of damaging—or even losing—that personal relationship. So to create a challenge network you have to overcome both conflict and loss aversion, which amounts to a risky proposition. But it may not be as risky as we think. In general, individuals believe that others will respond negatively when asked sensitive questions. We think it will come off as too personal, offensive, abrasive, or inappropriate. Compare questions like “How about this weather?” and “Did you catch that game last night?” with “Are you close with your parents?” or “What is something you struggle with?” While asking about the weather may not move the needle on a friendship, it runs no risk of damaging it either. However, research by Maurice Schweitzer shows that people are generally more open to these types of questions than we think. Further, there is a real opportunity cost of not asking sensitive questions because you never deepen that relationship, leaving relational capital on the table. Schweitzer’s takeaway is that the chances are slim that we will ruin a friendship by asking a sensitive question, and the benefits outweigh the risk of moving out of our conversational comfort zones. Applied to building a challenge network, you essentially have to reverse the order of the sensitivity. You are not asking for sensitive information about the person, rather, you are asking for critical feedback, which is sensitive information about yourself. Instead of asking “What do you struggle with?” you are saying “Please tell me what I struggle with.” This places pressure on the challenger, which is why we don’t like to do it. As a teacher, after a colleague observes my class, I may ask, “What did you think?” to which the auto-reply is “Great job!” Not much is gained in that interaction. But If I were to ask, “How do you think I could improve student engagement?” I might receive feedback that makes me a better teacher. However, immediately you can see the potential for conflict. Hearing something like, “You talk to fast,” “You don’t ask enough questions,” or “You use too much jargon,” may be simultaneously true and offensive, which is why we often default to the low-hanging fruit questions. But the opportunity cost here is self-improvement, and so it is in our best interest to overcome this obstacle. So how do you create this network? Consider the person you identified and follow these 8 steps:

Networks are essential to the human experience, but we tend to shy away from those that challenge us. Critical feedback is a necessary ingredient for personal growth, and the benefits of building a challenge network outweigh the potential risks. Find someone who will challenge you to be your best self. [Clip Art]

So let’s look at the terminology. According to dictionary.com, a coincidence it is “a remarkable concurrence of events of circumstances without apparent causal connection.” We are pretty familiar with this term. Let’s say you flip a coin five times wearing a hat and five times without, hitting five heads and five tails, respectively. This is a coincidence. The FBI defines a hate crime as a “criminal offense against a person or property motivated in whole or in part by an offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity.”

A coincidence implies correlation; a hate crime, causation. Flipping heads is perfectly correlated with wearing a hat, but wearing the hat did not cause you to flip heads. Alternatively, in a hate crime, a bias motivates not the crime itself but the choice of victim. If you can identify that the reason a crime was committed against a particular person is a bias against a group to which that person belongs, it can be classified as a hate crime. A hate crime, by definition, is not coincidental. The Atlanta shootings seem like more than coincidence. When 6 of the 8 victims are Asian women, a bias against ethnicity and gender seems likely. Put in context with the 3,800 attacks against Asians and Asian Americans since the start of the pandemic, it feels more like enemy action. However, it is difficult for a crime to be officially labeled a hate crime in part because it is challenging to prescribe someone’s motivation. Hate crimes against some groups are more obvious because they are often accompanied by a horrible symbol that underscores the motivation. The bias is less apparent for crimes against Asians and Asian Americans, but it doesn’t make it any less vile. In some ways, this obscured racism makes it an even tougher problem to solve. And the harder a problem is to solve, the more likely we are to be solution averse. The same way someone can be loss averse (we’d rather not lose $100 than find $100) or conflict averse (we’d rather eat the burnt steak than send it back), we can be averse to solutions (we’d rather avoid the problem than solve it). This seems counterintuitive. If something is wrong, the rational action is to fix it. If you break your arm, you get it set and cast. If you need a gallon of milk, you go buy it. If the grass is long, you cut it. But there are some problems we wish to avoid. And what is the simplest way to avoid a problem? Pretend it doesn’t exist. It can be something as simple as that noise your car engine is making (“I’m sure it’s nothing”) or the growing stack of paperwork on your desk (“I’ll get to it eventually”). But it also occurs with bigger issues, and is especially costly when the problem is shared by a group of people. It is much easier to deny climate change exists than try and find ways to address it. Racism is a problem that suffers from collective solution aversion. For some, it is easier to deny it exists, to sleep better knowing that it’s not real and therefore there’s nothing to be done. For others, the aversion may stem from the complexity and effort required. Like the equation on the chalkboard in Good Will Hunting, you just stare at it hoping someone else comes along to take care of it. You may wish you could solve it, but it is too complicated, too ambiguous, impossible. In the end, we are paralyzed by its complexity, so much that it no longer even represents a problem, rather it becomes a static part of life. You can’t erase it but you can’t solve it. It is just etched into the chalkboard of our subconscious. There is no doubt that as a country we struggle with different types of discrimination, racism, and misogyny, the institutional and structural centuries-long problems that manifest as inequality, poverty, etc. While recent movements have brought our attention to certain forms of discrimination (e.g., #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo), others are less conspicuous, such as discrimination against Asians and Asian Americans. However, this racism is now apparent. TV personalities making fun of Kamala Harris’s name pronunciation, the former President calling COVID-19 the Kung-Flu, attacks on Asians for ‘bringing the virus to the US’. In reality it’s not new, just more blatant. The same way that the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd made it impossible to ignore racism against the Black community, silence is no longer a luxury we can afford with our Asian and Asian-American community. It is a problem we cannot choose to ignore. As a country, we won’t ever ‘solve’ racism, but we can acknowledge the problem exists, and that it targets many groups of people. One step toward acknowledgement is getting the words right. Shooting six Asian women is not a coincidence. 3,800 attacks on Asians and Asian Americans since the start of the pandemic is not a coincidence. (The fact that the shooter is always white and always male—also not a coincidence). While motivations are inherently difficult to define, statistics are quite clear. Based on Ian Fleming’s quote, these events would be enemy action. Based on the FBI definition, they would be hate crimes. Based on the eye test, this is a problem, one shared by society, complex in nature, ambiguous in potential outcomes. It is a problem to which we cannot be solution averse because justice can only begin when ignorance ends. Unfortunately, there is no Matt Damon character to come along and solve this problem for us. But there is plenty of chalk to go around for everyone willing to try.

Psychologists call this the mere exposure effect. Essentially, the more familiar we become with something, the more we tend to like it or feel comfortable with it. This has positive repercussions. Has a person you didn’t initially get along with eventually ‘grown on you’? Did you used to hate broccoli? Did you think you didn’t like Taylor Swift until your wife convinced you to listen to her for an entire road trip? How much easier was your Zoom call yesterday than 11 months ago? Do you have quinoa in your pantry right now?

However, the mere exposure effect is not always constructive. For instance, do you like Tom Brady more or less after each Super Bowl? How do you feel about the company that airs the same commercial every fifteen minutes? On a scale of 1-10, what are your thoughts on snow right now? But the effect can be more adverse than dislike; it can create indifference, complacency. It normalizes things that should not be normal. Consider climate change. “Last year was the warmest on record” is a recurring phrase and, as a result, has lost its bite. Similarly, “X number of people died of COVID yesterday” blends into the background noise of our lives. The reporting of daily statistics is now familiar, and though we may not ‘like’ it, we have become comfortable with it. The mere exposure to these message has calloused us to their intended effects. At its worst, the mere exposure effect can desensitize us to lies and misdirection. The more something is repeated, the more it is believed—whether or not it is true. This is the evil cousin of the mere exposure effect known as the illusory truth effect. How many times have you heard that COVID-19 is no worse than the flu? Even though it is not true, we have become accustomed to the comparison. Subconsciously it is more conceivable, more palatable. The rhetoric of the last presidential administration has made us—not by choice—more comfortable with deceit and purposeful distraction. Each twisted fact, baseless claim, and outright lie consistently spewed from the White House dulled our senses, numbing our reactions. But the most hopeful outcome of the mere exposure effect is that it normalizes things that should be normal. The most salient example of this came watching the inauguration last month. During the ceremony, they mentioned how Kamala Harris was the first Black person, first Asian, and first woman to hold the office of Vice President. Further, she was sworn in by the first Latina on the Supreme Court. I was waiting for banners and confetti to drop. However, the coverage quickly moved to Joe Biden—the 46th consecutive male and—with the exception of Barack Obama—white president. At first, I was disappointed. It felt like the terrorist attack on the Capitol, coupled with four years of discord and dissension, overshadowed the magnitude of the moment. This was historic, this showed progress from a nation which, at other points over the past four years, seemed to be slipping backwards in time. We needed to be shouting this from the rooftops: Look what we can do, look how we have changed, how far we’ve come in the 100 years since the 19th Amendment was ratified. However, these thoughts quickly shifted. Something isn’t normal if you have to announce it or point it out, and women Vice Presidents should be normal. We will be in a better place when this is not newsworthy, when we have a second, third, fourth women President, an umpteenth Black President, an ‘I-stopped-counting’ LGBTQ+ President. This important because the mere exposure to someone like you doing something you want to do instills confidence. Years ago I was given a book called What the Best College Teachers do. On the cover is a white middle-aged man with graying hair, and the author is also a middle-aged white man with graying hair. The takeaway: college professor is a profession for someone like me. I have been exposed to tailwinds like this my whole life, which makes me feel more comfortable pursuing this career. It feels not only achievable but expected. Just as we had eight years to watch Barack Obama address the world as President of the United States, we now have four years to watch Kamala Harris as Vice President (and potentially President in 2025). The fact that it is already becoming less newsworthy shows we are on the right path. We don’t make a fuss over trivial things, we expect them, and President should a normal, achievable, even expected career path for every U.S. citizen. Familiarity breeds comfort, and there are certainly things that seem crazy today but will one day seem mundane. Maybe Bud Lite will reboot their burger commercial with crickets replacing quinoa? Maybe Taylor Swift will be your most-listened-to-artist on Spotify next year? Maybe we’ll want to wear masks on a plane? But more importantly, the mere exposure effect can convey that what once seemed impossible is anything but. It can normalize what should be normal. Bug burgers can wait, but hopefully very soon we will not feel the need to count how many female or Black or Asian or Latina or LGBTQ+ people are CEOs or head coaches, members of Congress or members of SNL, or President of the United States. According to thermodynamics, chaos is the natural evolution of any isolated system. That is, things tend to become more—rather than less—chaotic over time. Molecules default to speeding up rather than slowing down, creating energy, randomness, and disorder. Entropy, or this degree of randomness, will never decrease in an isolated system unless influenced by the external environment. A glass of water tends to get warmer, not colder, as the molecules speed up and create thermal energy. The only way for the system to lose heat is if something outside the system (e.g., an ice cube) acts upon it to absorb some of that energy. The heat is not lost, just transferred.

Like the glass of water, everything in the universe gradually declines into disorder, or entropy. Think about your kitchen utensil drawer or vegetable garden. If you don’t actively manage them, will they become more ordered or more disordered over time? But there is an edge of chaos, a point right before complete disorder, and January 6 could represent that edge of chaos in the United States. Amidst the pandemic, a fumbled vaccine rollout, a new, more contagious strain of the virus, the highest death & infection rates, and the general effects of social isolation and fear, we had a domestic terrorist event where armed insurrectionists breached the capitol upon instruction of the president. America had reached the edge of chaos. This was not a shock. It was the natural, expected progression of the entropy brought on by Trump, or what I call enTrumpy. Its molecules (i.e., his loyalists) have been increasing in energy for years, moving closer and closer to complete chaos and disorder. Applying the second law of thermodynamics, the expected result of ever-increasing enTrumpy is a climactic event thrusting us to the edge of chaos, a glass or orange water reaching its boiling point. Ironically, while Trump has touted ‘law and order’, that is precisely what he avoids. From day 1, he has embraced the quote from Petyr Baelish, using disruption and chaos to climb the ladder to the Republican nominee and presidency. Law and order means that events are predictable, they follow a pattern. That way to power is more like a staircase, with each step requiring competency and governed by decency and reason. Power through chaos is a free-for-all where the strongest grabs the first rung on the ladder, climbing with disregard for rules or decorum. Essentially, Trump has always known that if shit hits the fan, anything can happen, so he keeps slinging it up there. He’s like a child at a party given the first crack at a piñata. He knows there are rules, but instead peaks under the blindfold, busts it open, and grabs all the candy for himself while wielding the bat. Sprinkle in some name-calling, narcissism, a big ego, hate speech, and you have yourself a bully. A bully creates chaos to gain control and achieve power. The events of last four years prove this point. Each hate-filled Tweet and lie-filled video was a rung on his ladder to power and dissension. (It’s no coincidence that some of the flags at the incited terrorist attack had the flag of a fictional country, Kekistan, named for Kek, the god of chaos.) But we have not reached complete chaos. We are at the edge. Chaos theory says that organisms self-adjust at the brink, employing creativity, flexibility, and innovation to avoid chaos. This is known as ‘adaptation to the edge of chaos’, and humans have already shown our capacity to adapt. Think about the creativity, flexibility, and innovation displayed across the global community to avoid complete chaos from the COVID-19 pandemic. So how can we come back from the edge of Trump’s chaos? How can we decrease the enTrumpy in the glass of water? We drop in ice cubes, i.e., we give him the silent treatment. Silence is often characterized as cold. We give someone ‘the cold shoulder’. A terse reply is ‘chilly’. You ‘ghost’ somebody by ending all communication with them—how cold! We can transfer the heat and energy away from him simply by not giving him the space in our minds or mouthes that he has fed on the past 4 years. Giving voice to a person is a choice. We chant ‘Say His Name’ and ‘Say Her Name” to make sure we don’t forget George Floyd or Breonna Taylor. Silence is not an option with #BlackLivesMatter. Conversely, Donald Trump is a name I hope we never have to say or hear again. The best way to take power away from a bully is to ignore them. If the other kids simply walk away from the piñata—or don’t invite the bully to the party—the power dissipates. Loyalists praying to their fake Trump god will realize his America is just as fictional as Kekistan. As the silence grows, the rungs on his ladder will get more and more slippery. Trump certainly needs to be held accountable, responsible, and liable for his actions, but we do not owe him our collective headspace. While it is natural to enjoy watching the powerful fall from grace, it isn’t helpful for a country trying to restore itself to order and civility. Starting January 21, we shouldn’t need to think about him anymore—courts and governments will take care of all the messy bits. Trumpism is not going away. It is only a matter of time before a savvier, more capable disciple takes up the mantle. Once again a strong, unified voice will be required to keep us from the edge of chaos. But in this moment, silence may be our loudest expression, an ice cube to slow down enTrumpy. |

AuthorColin Gabler is a writer at heart. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed