Take the group of folks who are simply working from home, getting paid the same salary, dealing with a dog barking on your Teams Meeting, COVID-19 is an inconvenience. Sure, some may get sick themselves and they will absolutely know someone who gets sick, hospitalized, and probably somebody who dies from the Coronavirus. I do not want to minimize the overall impact across the board. This virus does not discriminate; however, humans still do.

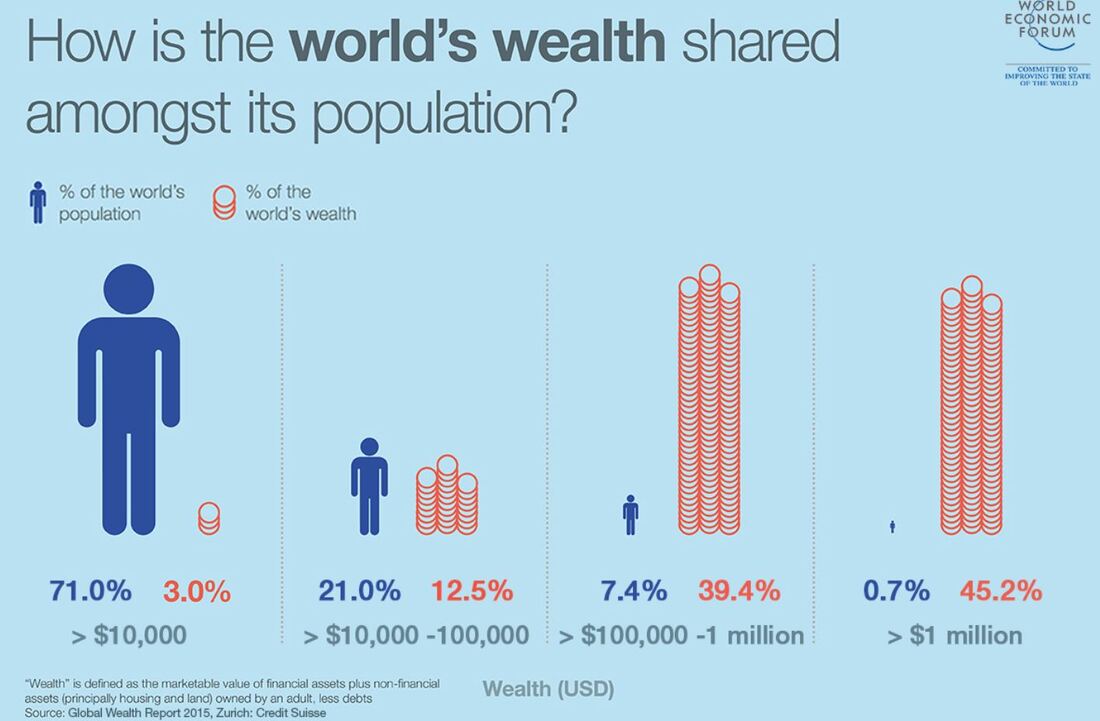

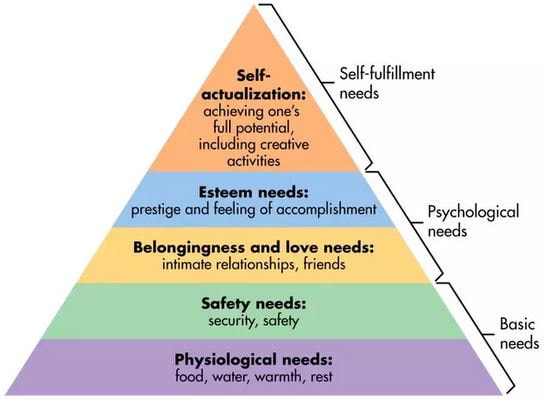

Now consider an example from another group of people. A couple with 3 kids who rent a house and both parents hold service positions at a restaurant. For this family, the situation is grave. The restaurant and school both closed, which increased their personal costs while eliminating their revenue source. Or consider the single parent who works at the grocery store who is ‘allowed’ to work—and might even see increased hours. Being an essential employee allows her to earn an hourly income, but she is exposed to the Coronavirus. Given financial burdens, she doesn’t have a choice. Sure, her place of employment has been labeled ‘essential’ by the government, and so she can earn money, but she might choose to be nonessential. Both examples are more likely than the first group to live in closer quarters, to rent an apartment, have less access to healthcare, less savings, and fewer safety nets in general. There is, of course, a third tier of increased susceptibility. It is sobering to consider how this virus will spread through the most vulnerable of us, people in prisons, nursing homes, patients in cancer wards and with immune-deficiencies, and our growing homeless population. For these individuals, there is literally be no escape and no option. None of this is new to the dialogue, however, I wonder if the COVID-19 pandemic will expose the inequality that exists in our world. If the misnamed Spanish Flu from 1918-1919 is a benchmark, then it absolutely will. However, given the stresses of World War I, many government officials and public news outlets did not want to present more bad news, and so the inequality was largely forgotten about soon after. In fact, it was the Spanish government who first presented real data on the situation, leading to the perpetually misnomer of the strand of influenza itself. In 2020, we do not have a global war to detract attention from the pandemic or the glaring inequality that it highlights. In my sustainability marketing class, we go over all of the factors that contribute to the current problems we face. Global income inequality is not often on the top of mind, but the class quickly comes to a consensus of its role. The stats are always changing and always staggering. For instance, as of December 2019, the top 26 richest individual people hold as much wealth as the bottom 3.8 billion. [That one deserves a second look, but when you consider that 1+ billion people live on less than $1 per day and Jeff Bezos has 107.3 billion dollars, it adds up]. These eye-popping numbers go on and on. In normal times, socioeconomic status is related to outcomes such as quality of life and life expectancy, but we are about to witness just how negatively correlated the variables can be. For those of us who are somewhat insulated, who have the privilege to social distance, is there something we can do? There is a lot of rhetoric about what is going on in relation to COVID-19, and hopefully we begin to ask what are potential ‘silver linings’? We’ve already seen this happening with reduction pollution in China, but what are some other social aspects that we can address in this time of crisis so that when things get ‘back to normal’ we do a better job at protecting those of us who need protection? I don’t suggest that any true good can come from a global pandemic; it is just putting a lot of social institutions under the microscope. Some for better and some for worse. Regardless, we won’t be able to justify our global imbalance when it is so blatantly in our faces via red numbers on a ‘death toll’ screen. In summary, is this just a “Them’s the breaks, kid” situation for certain people beneath an arbitrary socioeconomic divide or do we have a responsibility to shift the paradigm? If the latter, how? John Rawls Theory of Justice is a good starting point.

24 Comments

Because I teach courses in business and professional development, every semester, we spend a few minutes discussing the keys to a professional handshake. Not too firm, not too soft, the correct number of ‘ups-and-downs’, dry your hand if it is clammy, etc. No lobster-claw, dead-fish, leave-ya-hangin, pass-the-teacup, bone-crusher, southpaw, Queen’s fingertips, fist bumps, chest bumps, high-fives, high-fives-into-low-fives, high-fives-into-foot-grabs, bro-hugs, halfsies, limpsies, etc. I put importance on this task because it is often the only physical contact we have in a professional relationship. It seems crazy to even type this right now, but I usually have students shake the hands of ten other students. (My classes can attest this semester—about 6 weeks ago now—I refrained from this exercise. Not due to Coronavirus but simply to not spread any germs around a class of 150 students). Suffice it to say, I think this is an important skill that requires practice and attention. While the do’s and don’ts of handshaking seem obvious, I’m always surprised by the learning that takes place in this lesson.

Now that we cannot (or should not) be within 6 feet of each other, let alone shake hands, what other ways can we connect? Waving, smiling, and eye contact. The gesture of a wave is built into our culture from a young age. You wave goodbye to your parents when they leave for work. Santa Claus waves from a faux chimney during the holiday parade on Main Street. You wave as your kid goes off to college. And if you are like some wonderful folks I know, you wave when someone drives away from your house until they are literally past the horizon or around the corner and you can’t see them anymore. Smiles are even more a part of our culture (in the US, at least, this is not the case in other countries—but that is for another blog post). We get excited the first time a baby smiles and we decide whether or not it is worth asking someone out on a date based on a reciprocation of a smile across the proverbial crowded room. Universities and trainings even teach subtle smiling nuances in our professional development classes to help people ace the interview. Eye contact is crucial to non-verbal communication. It demonstrates that you are engaged in a conversation, that you are actively listening to a person speak, and allows you to convey empathy. Too little can show disinterest or lack of trustworthiness. Too much can be threatening or downright creepy. But we each calibrate to the other person to effectively achieve the correct recipe for the situation. It puts us at ease and makes the conversation comfortable. In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, handshakes are out. Smiling, waving, and eye contact are in. Or are they? My assumption was that given the social distancing taking place all across the world, human nature would lead us to do more of these three things. Online meetings and conference calls do not allow for physical touch, so we are making do with our other tools. We even have a name for the smile/nod combination we all do at the beginning of a Zoom or Teams meeting: the ‘virtual handshake’. However, anecdotally, this has not translated to my in-person interactions. Living in a small college town, (now emptied of half of its population when students were sent home), I take to the bike path almost every day for a long walk or run, and I’ve been doing an observational analysis. I try to make eye contact, smile and/or wave at every person I see. You know, the little half up wave, maybe a slight nod or ‘hey’ as you pass someone. My prediction was that more people would reciprocate than, say, last fall when I was on the same bike path doing the same walks or runs. Being bottled up in our homes, practicing social distancing, self-isolating, etc., led me to believe we would crave more interaction (as fleeting as a wave or smile) when we were out in the world. Unfortunately, I did not start this study last fall to provide a control, making this completely unscientific study even less credible, but I have been surprised in the 1:4 ratio of people who reciprocate with a smile, wave, or eye contact versus people who a) look away, b) look at their phone, c) meet my eyes but quickly look away, d) or ignore me all together. Now granted, there are a lot of biases and other extraneous variables at play here. And yes I am aware that I might be known as the weirdo on the bike path who waves at everyone, but I was surprised by this result. Perhaps fear has trumped (hate to use that word) the longing for social connection? We associate friendliness with engagement, which we associate with human interaction, which is what we know spreads this virus. Perhaps in that split second as I run (super fast) by the other person, fear bubbles to the surface just ahead of the need to socially interact. Maybe that gut instinct is “human interaction=bad” followed closely by “human interaction=good/great/essential.” Who knows, maybe if I turned around, they’d all be waving and smiling back. I like to think so.

|

AuthorColin Gabler is a writer at heart. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed