So let’s look at the terminology. According to dictionary.com, a coincidence it is “a remarkable concurrence of events of circumstances without apparent causal connection.” We are pretty familiar with this term. Let’s say you flip a coin five times wearing a hat and five times without, hitting five heads and five tails, respectively. This is a coincidence. The FBI defines a hate crime as a “criminal offense against a person or property motivated in whole or in part by an offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity.”

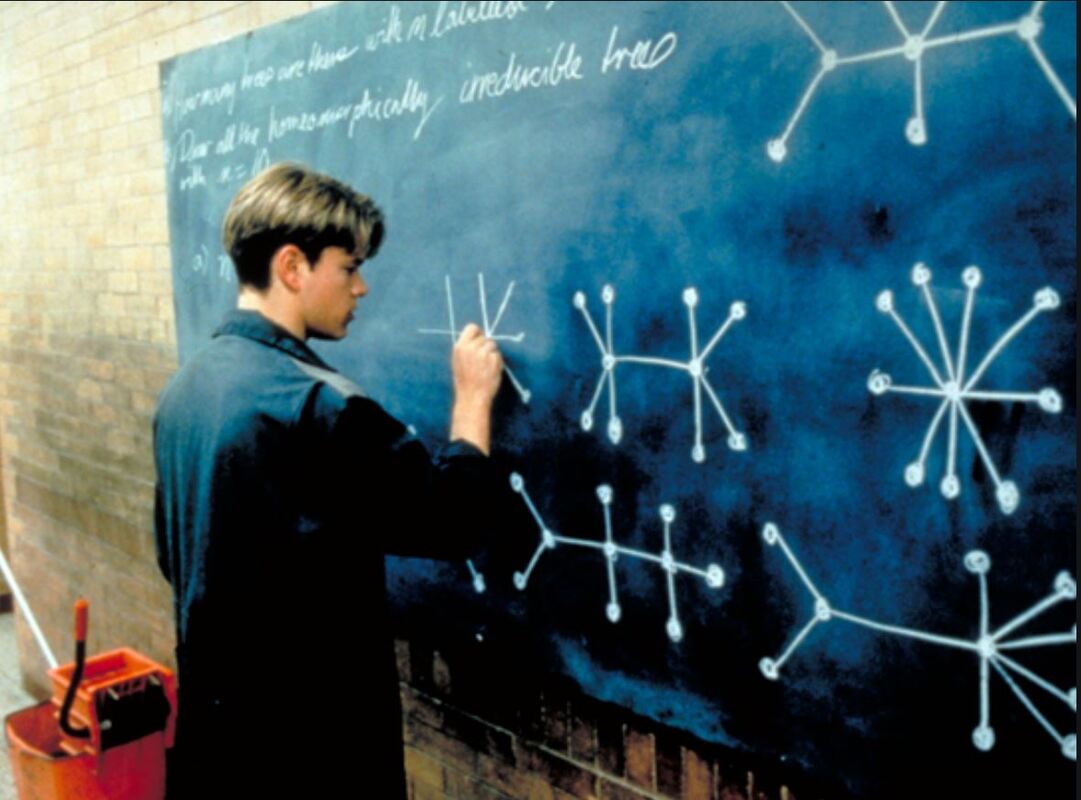

A coincidence implies correlation; a hate crime, causation. Flipping heads is perfectly correlated with wearing a hat, but wearing the hat did not cause you to flip heads. Alternatively, in a hate crime, a bias motivates not the crime itself but the choice of victim. If you can identify that the reason a crime was committed against a particular person is a bias against a group to which that person belongs, it can be classified as a hate crime. A hate crime, by definition, is not coincidental. The Atlanta shootings seem like more than coincidence. When 6 of the 8 victims are Asian women, a bias against ethnicity and gender seems likely. Put in context with the 3,800 attacks against Asians and Asian Americans since the start of the pandemic, it feels more like enemy action. However, it is difficult for a crime to be officially labeled a hate crime in part because it is challenging to prescribe someone’s motivation. Hate crimes against some groups are more obvious because they are often accompanied by a horrible symbol that underscores the motivation. The bias is less apparent for crimes against Asians and Asian Americans, but it doesn’t make it any less vile. In some ways, this obscured racism makes it an even tougher problem to solve. And the harder a problem is to solve, the more likely we are to be solution averse. The same way someone can be loss averse (we’d rather not lose $100 than find $100) or conflict averse (we’d rather eat the burnt steak than send it back), we can be averse to solutions (we’d rather avoid the problem than solve it). This seems counterintuitive. If something is wrong, the rational action is to fix it. If you break your arm, you get it set and cast. If you need a gallon of milk, you go buy it. If the grass is long, you cut it. But there are some problems we wish to avoid. And what is the simplest way to avoid a problem? Pretend it doesn’t exist. It can be something as simple as that noise your car engine is making (“I’m sure it’s nothing”) or the growing stack of paperwork on your desk (“I’ll get to it eventually”). But it also occurs with bigger issues, and is especially costly when the problem is shared by a group of people. It is much easier to deny climate change exists than try and find ways to address it. Racism is a problem that suffers from collective solution aversion. For some, it is easier to deny it exists, to sleep better knowing that it’s not real and therefore there’s nothing to be done. For others, the aversion may stem from the complexity and effort required. Like the equation on the chalkboard in Good Will Hunting, you just stare at it hoping someone else comes along to take care of it. You may wish you could solve it, but it is too complicated, too ambiguous, impossible. In the end, we are paralyzed by its complexity, so much that it no longer even represents a problem, rather it becomes a static part of life. You can’t erase it but you can’t solve it. It is just etched into the chalkboard of our subconscious. There is no doubt that as a country we struggle with different types of discrimination, racism, and misogyny, the institutional and structural centuries-long problems that manifest as inequality, poverty, etc. While recent movements have brought our attention to certain forms of discrimination (e.g., #BlackLivesMatter, #MeToo), others are less conspicuous, such as discrimination against Asians and Asian Americans. However, this racism is now apparent. TV personalities making fun of Kamala Harris’s name pronunciation, the former President calling COVID-19 the Kung-Flu, attacks on Asians for ‘bringing the virus to the US’. In reality it’s not new, just more blatant. The same way that the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd made it impossible to ignore racism against the Black community, silence is no longer a luxury we can afford with our Asian and Asian-American community. It is a problem we cannot choose to ignore. As a country, we won’t ever ‘solve’ racism, but we can acknowledge the problem exists, and that it targets many groups of people. One step toward acknowledgement is getting the words right. Shooting six Asian women is not a coincidence. 3,800 attacks on Asians and Asian Americans since the start of the pandemic is not a coincidence. (The fact that the shooter is always white and always male—also not a coincidence). While motivations are inherently difficult to define, statistics are quite clear. Based on Ian Fleming’s quote, these events would be enemy action. Based on the FBI definition, they would be hate crimes. Based on the eye test, this is a problem, one shared by society, complex in nature, ambiguous in potential outcomes. It is a problem to which we cannot be solution averse because justice can only begin when ignorance ends. Unfortunately, there is no Matt Damon character to come along and solve this problem for us. But there is plenty of chalk to go around for everyone willing to try.

0 Comments

|

AuthorColin Gabler is a writer at heart. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed