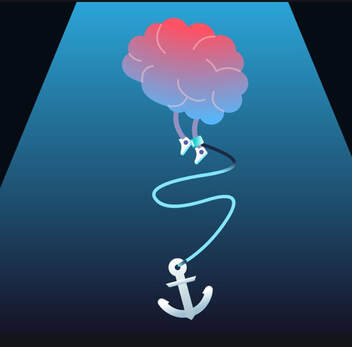

Essentially, we are biased to the first piece of information we receive, placing more value on it than subsequent information. This initial data point acts as the ‘anchor’ from which all other information is weighed and judged, and ultimately it impacts the final decision. We do this all the time. Think about what you would pay for a bottle of wine, a T-shirt, a gallon of milk, etc. You have established a reference price for these products based on past experiences, and you are now anchored to them. It can be an effective decision-making tool. If a gallon of milk cost $1 or $10 you would think something is up. Retailers know this as well. When a product goes on sale, why don’t they remove the old price and just show the new one? Because they know consumers like to see “Was $20 – Now only 10!” If we are anchored to the larger price, the smaller price conveys that we are gaining more value in the exchange.

How does this apply to early voting? A recent The Daily podcast entitled “The Shadow of the 2000 Election,” talked about that infamous election was shaped by Gore conceding when the results were still in question. From thereafter, it was a Bush victory with Gore contesting the results; instead of an undecided election with both candidates calling for a recount. In the collective mind of the country—and propagated by the media—America had chosen a president, and now Gore seemed like a sore loser. This perception was shaped by Bush being anchored as the winner in the minds of US citizens. This made any efforts from Gore incredibly challenging because he was playing from behind. Our initial impression of the electoral results had been made, and it was incredibly challenging to overcome. In my sales class, we discuss the importance of first impressions. When we encounter a new person, we have somewhere between 3 and 30 seconds to make our first impression. Every interaction afterward moves our assessment from that starting point—that anchor. That is why they are so important. If you begin a job interview my mispronouncing the name of the company, you have an uphill battle to gain any sort of credibility. If on your first date, you beep from your car and s/he runs through the rain to get in, you also have set the bar quite low. In both cases, you have anchored yourself low on the continuum of ‘good employee’ or ‘good date’ and have to move from low to high. You have also created a ‘halo effect’, where the interviewer or your date will make assumptions about other aspects of your character based on that snap judgment. Imagine instead that you start the job interview by correctly pronouncing the company name and a few specific, hard-to-find facts that made you want to apply. Or if you rang the doorbell, escorted your date under an umbrella, and opened the car door. Here you dropped anchor at a much more favorable place on the continuum. The same halo effect will occur, only this time it works to your advantage. The employer may assume your preparation means you are also a critical-thinker. Your date may translate your courtesy to integrity. And given the confirmation bias (another blog), both parties may look for ways to affirm those positive [or negative] attributes to keep you close to the initial anchored perception. Back to early voting and the 2020 election. As of this writing, over 66 million early votes have been cast, which points to record levels of voter turnout. This is important because when the first projections are released, we will have our reference point for the rest of the election. We will be anchored to the initial leader, making subsequent judgments from that first impression. If you are thinking that this shouldn’t matter, you are correct. Votes are tangible, simply count them up and don’t worry about perceptions. But it very well might matter for two reasons. First, President Trump has made it clear that he is willing to do anything to throw this election into turmoil. As Petyr Baelish says in Game of Thrones, “Chaos is a ladder,” and Trump embodies this idea (e.g., his Coronavirus response). The closer the initial results, the easier to poke holes in them. absentee ballots, voter fraud (, etc. The wider the margin, the harder it becomes to challenge the results. At some point, even the most narcissistic person must come to grips with the will of the people. This first impression, then, has the ability to give momentum to either campaign. Secondly, while there is no evidence that voter fraud is even a thing, the term has somehow gained a foothold in the American vernacular (again, stemming from the 2000 election). This is important because this election will be—and to some degree, already has been—decided by courts and the legal system. Make no mistake, Trump’s best prospect at re-election is through litigation, and once again, perception matters. Trump has challenged voting by mail, drop boxes, absentee ballots; he has added restrictions to disproportionately impact minority communities; he has sued states for allowing votes to be counted after certain days; he has sued governors to stop expanded mail-in voting; he has appointed countless judges to do his work for him (e.g., a New Jersey judge decided to ‘throw away’ 50,000 ballots—which is a big deal considering Trump won 2016 by 77,000 votes). The goal of all of these actions is to reduce the number of presumed votes for Biden. Plain and simple. The best way to counteract is to be so overwhelmingly ahead, that even the courts cannot come to the rescue. In normal times, we would all sit back and think about how crazy it is that the President of the United States is actively trying to limit the ability of its citizens to vote. Somehow in 2020, that is a given, and so we have to instead think of ways to overcome this dictatorship-adjacent move. That is why early voting matters. The more we can anchor the perception of a Biden win in the minds of the citizens, the harder it will be—even using purposefully deceitful tactics—to move the anchor. Regardless of the initial results, the Trump administration will challenge the methods, the media, the poll workers, governors, state laws, ballots, even voter intentions, so we should try to make it as wide a gap as possible to overcome. The heavier the anchor, the harder it is to move.

1 Comment

Reflecting on this and with an impending election, another mechanism came to mind as a tool to understand irrational behavior regarding our choice in November: the sunk cost fallacy. It’s important to clarify now that while this will pertain to Joe Biden versus Donald Trump, it is not an election-specific idea. The premise is simple and particularly relevant in a system where elected leaders can serve two (or more) terms and in a society where our political identities are focal points in social dialogue. So first, what is the sunk cost fallacy? Imagine you go to the movies (I know this requires real imagination in 2020). You pay $12.50 for a ticket, settle in your seat, and the lights go down. The movie starts slow, then gets confusing, the plot is disjointed and the characters one-sided. About halfway through, you realize: this is a bad movie. Now ask yourself, would you a) walk out or b) finish the movie? If you are like most people, you would finish the movie. Why do we do this? If the movie is two hours, you could use that second hour for anything: call your mother, do some laundry, meet a friend, read a book, even start watching a good movie. One reason we ‘stick it out’ is due to the sunk cost fallacy. This is irrational behavior. You cannot ask for a reimbursement of $6.25. The entire $12.50 is gone forever and, therefore, should be irrelevant to the decision to finish the movie. The first hour is also gone and should theoretically hold no bearing on how you spend the second. However, we want to ‘get what we paid for’, and so we push on. This is a common influence on our decision-making. Consider an all-you-can-eat buffet. You pay up-front and that money has been irrevocably spent before your first bite. At that point, the rational individual wishes to maximize utility by eating a satisfying meal. However, we keep adding to our plate wanting to make the most of the sunk cost. We knowingly decide to feel worse later (food coma, indigestion, etc.) for the knowledge that we got our money’s worth now. This is common in relationships. How many of us have a friend or relative that detracts from our overall happiness, yet we continue the relationship because ‘we have been friends for twenty years’? Or the toxic friendship that you don’t quit because you’ve put in the work and don’t feel like starting over. You’ve made relationship investments that provide no returns, but rather than cut your losses, you stick it out, hoping to eventually get that ROI. This concept can be applied to all elections, but I’ll focus on this November. In 2020, our political affiliations are worn on our foreheads. This can be quite literally as wearing a bright red ‘MAGA’ hat or less literal as putting a #BlackLivesMatter sign in your yard. There is a general consensus that he will be objectively considered one of the worst presidents in U.S. history. It is reasonable, then, for 2016 Trump voters to feel cognitive dissonance, and implement logic to justify the decision. “He speaks his mind and I like that.” “I’m just happy he’s not another politician.” “He’s a good businessman” (a now debunked claim). That is what makes it possible to hold two realities in your mind simultaneously. The sunk cost fallacy enters the scenario when we have a chance to make a very similar choice: the 2020 election. The next vote could act as an extension of the dissonance created by the first vote, providing an opportunity to reconsider the choice. The options are to double down on the initial bet (Trump) or vote from a clean slate without considering the bet you made in 2016 (Trump or Biden). The key is to not think about your 2016 vote as a mistake—or to think about it at all. That only creates cognitive dissonance and has no bearing on how you vote in 2020. But the sunk cost fallacy will compound the cognitive dissonance associated with the 2016 Trump voters and lead them to vote for him again in 2020. Meaning, rather than view the upcoming vote as its own distinct decision, Trump voters may see it as a continuation of their 2016 vote. By voting for him again, it affirms that they made the right choice the first time (why else would they vote to re-elect him?). While irrational, we do this all the time. Consider when you have taken one side in a friendly debate and slowly realize that either you are wrong, you had incorrect data, or you actually agree with your opponent. Which is easier to do: change sides or continue holding your ground? I can relate. Let’s return to the movie analogy. When Star Wars: The Phantom Menace came out in theaters in 1999, I was beyond excited. I thought it was going to be the greatest movie of all time. I wore a Jedi robe to the midnight show, walked in the theater, cheered when the lights went down, and then it started. As everyone knows, it was pretty terrible (apart from Darth Maul). However, not only did I not leave the theater, I decided I would profess that I loved it anyway and, to validate the point, I would return to see it ten more times in the theater. Each time—and yes I really did go 11 times—I entrenched myself as a staunch supporter of the movie, even though I knew it was bad. And each time, I accrued 2 hours and 16 minutes more of the sunk cost of initial decision, requiring more effort to overcome my cognitive dissonance. All you have to do is replace the movie title with Donald Trump, the Jedi robe with MAGA hat, and Darth Maul with the pre-COVID Stock Market, to see how tough it can be for a 2016 Trump voter to not vote for him in 2020. I do realize that many people who voted for Trump think he is a great president and will be proud to vote for him again. I just hope that the small number of people who voted for him in 2016, but wish they hadn’t, will not let a sunk cost determine a future decision. Your choice in 2016 holds no bearing on your choice in 2020. The beauty of elections is that they are distinct. You do not have to proclaim that a previous vote you made was wrong or that you are switching sides, you simply have to vote in the current election using your best judgment. By the same token, nobody should vote for Biden purely because they voted for Hillary in 2016. Their choice should also not be a continuation bet, but instead a frank evaluation and discrete decision. Every election is a chance to wipe the slate clean and make a new determination. This one is important and needs our most rational cognitive decision-making capabilities. |

AuthorColin Gabler is a writer at heart. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed