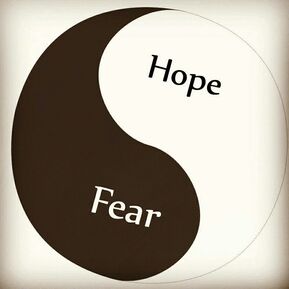

This dichotomy recalled an episode from ‘The Weeds’ podcast. Essentially, they broke down our two political parties into similar groups using one word descriptors: Democrats=hope and Republicans=fear. Thinking about the words objectively, this resonated with me because of its simplicity and—in my opinion—its accuracy. As the podcast noted, you only have to look at the last two winning presidential slogans. Barrack Obama used “Hope and Change” while Donald Trump used “Make American Great Again.” The former seemed to view the changing global landscape as something to be hopeful about. The latter seemed to suggest that things were better ‘back in the good old days’. Obama sought change while Trump longed for the status quo, or rather, what used to be the status quo.

Both men were looking at a similar situation: the unknown. Where is the United States heading? What is our American identity? How should we handle issues such as immigration, systemic racism, economic issues, foreign affairs, inequality, human rights, etc.? They just viewed the situation through different lenses. You could argue (as pundits do) which is the correct lens, but the important thing is that the same basic picture can be framed so dramatically differently. Most people identify with both hope and fear in some way. How do you answer the question: what does the future look like? Is your answer “Things will get better,” “Things were better before,” or somewhere in the middle. You could call these liberal or conservative values, but both can be useful—now more than ever. To borrow the cliché, in the midst of this pandemic, we need to work across the ideological aisle as we think about next steps. We need to balance a sense of hope and fear. Fear can be a good thing. We are familiar with the fight-or-flight response to a dangerous situation. Scholars suggest this phenomenon evolved from our time on the plains thousands of years ago. Sensing a predator in the high grass, we quickly determined it was time to retreat to safety. This instinct evolved to ensure our survival. Today, we are fearful of an invisible virus that spreads easily and indiscriminately while harming and killing discriminately. This fear also evolved to ensure survival. If we did not fear the Coronavirus, we would fall victim just as we would have to a lion on the savanna. Fear can be a bad thing. However our fear manifests (anxiety, stress, doubt, suspicion, despair) it acts as a self-imposed limitation on our potential. We can become paralyzed by it and miss opportunities. Often a difficult or threatening situation reveals our most admirable qualities, from standing up to a bully to speaking in front of a group. Overcoming fear shows courage and resolve. Fear is omnipresent right now, and while it is certainly helpful, succumbing to it hinders our resilience. Hope can be a good thing (the character, Red, from The Shawshank Redemption would argue “maybe the best of things”). Without hope, the future is bleak, but hope is more than optimism. The optimist wants to believe the future will be good. The hopefulist (patent pending) actually expects it. We hope that the spread will slow, we hope that therapies, drugs, and vaccines will come to market quickly, we hope for the restoration of ‘the new normal’. This provides us with a sense of purpose to continue in our day-to-day lives, to pursue goals, and put things on the calendar. Hope can be a bad thing. Like fear, hope can lead to inaction if we feel as if the hard part is already done. Hope without action is not a strategy, it is wishful thinking. Hoping that your dog will sit, stay, and roll over will not lead to a well-behaved pet. It requires training. Hoping that someone will ‘figure out’ climate change will not reduce global temperatures. It requires massive coordinated effort. Hope provides the direction, but action gets you to the destination. Expectations can indeed be great—if you do something to make them happen. As countries, states, counties, and cities unveil their new guidelines and phases of reopening, our society faces a major test, and like a final exam in school, both fear and hope can be beneficial if used appropriately. If you are paralyzed by a fear of failing, you probably will, and if you are purely hopeful that you will earn an A, you will probably not. Hope and fear are static; they require action to be useful. If your fear motivates you to talk to your teacher and your hope motivates you to study harder, you will succeed. Perhaps hope and fear are two sides of the same coin. If so, there is value to be gained from both heads or tails if a healthy balance can be achieved. We can use our fear to take precautions and safety measures, to avoid unnecessary risks, and save each other’s lives. But we can’t allow it to make us feel helpless. Similarly, we cannot hope the virus away, but we can leverage our hope to maintain positivity, to offer encouragement to those who need it, and to help our communities recover for a future we expect. We have the ability to activate the positive motivations from both hope and fear, which can give us control over the situation. Because in some ways, ‘things were better before’ but ‘things will get better’.

1 Comment

Sometimes this trust is earned. Consider your friend who has built it over decades or the medical expert through education and practice. But in the case of driving down the highway, we give it without a second thought. This implicit trust is a good thing. It is what makes our society so livable. We make assumptions that our fellow man and woman will take the ethical high ground. And with rare exceptions, this trust is warranted and reciprocated. Imagine a world where it didn’t exist, a lifetime filled with anxious moments wondering if someone was holding up their end of this unspoken agreement.

This baked-in trust is fundamental to a benevolent civilization, but in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic—when you could argue it is most needed—I feel as if it is in jeopardy. Consider any news program, social media post, or press release. Do you trust the reporting and the statistics? Do you trust the data and its interpretation? Do you trust the person providing the information? If you answered No, that is probably a good thing. For instance, if you trusted President Trump in February, you thought the virus would be miraculously gone by now and we’d have a vaccine, if you trusted him in March, you thought the flu was worse than the Coronavirus and everyone would be tested by now, and if you trusted him in April, you might have literally drunk bleach. If you trusted Beijing’s initial reports, you’d believe Coronavirus killed far fewer people than it actually did in Wuhan. If you trusted the Bakersfield doctors, you would have too much mis-extrapolated information to even process. If you trusted certain memes, you’d believe that dolphins are swimming in the Venetian canals. In some cases, finding out that we shouldn’t have trusted the source is fairly benign and non-consequential (if you want to daydream about dolphins squeaking while jumping over the Rialto Bridge, what harm is there in that?). But the others are breeches of our trust with the potential for catastrophic consequences. Trust is wholly dependent on truth, and like so many virtues, it can take a lifetime to build and seconds to evaporate. Truth, likewise, depends on trust. We tend to only speak our deepest truths to our most trusted friends or proven experts. But we also trust, more generally, that we, as humans, are all playing for the same team. We default toward trusting that we will individually take the high road for the collective good. Part of what keeps our societal fabric so tight is the thread of freely-given trust woven throughout it. And that is why our cultural trust is in jeopardy. When we cannot trust that public officials, medical experts, the media, and the President of the United States, are playing for the same team, who do we turn to for leadership? Now is not the time for our basic trust in each other to erode. Over the coming months, treatments and vaccines are going to be available. We need to trust public health officials to make the ethically appropriate decision on distribution measures. Incidentally, there is no ‘right’ way to do so. One could argue first-come-first-serve, life years, quality of life, best chance of survival, instrumental societal value, among others. The key here is that we trust medical ethicists to make the best decision given the set of parameters. Further, there are many more viruses like this that could strike down the road. We need to trust that our government will fund the studies to get ahead of the next crisis. We need to trust that when our governor issues another month of social distancing, he or she has our interests in mind and is not motivated by political reasons. We are going to have to trust that our education system is actively looking for creative way to engage students. On a personal level, one day we are going to go to a pub to meet friends. Like passing drivers on the highway, we will have to trust that everyone has taken proper precautions or they wouldn’t be there. Skepticism is not inherently bad. Skepticism can further discussion, spur debate, and lead to an optimal course of action. Cynicism, on the other hand, offers little value. It halts discussion, ends debates before they start, and leads to self-interested action. However, it is becoming more prominent with every news cycle. While conspiracy theories, fact-massaging, convenience sampling, and ulterior motives are nothing new to 2020 or COVID-19, they have been accentuated by the current imperative for information. This makes us more vulnerable to losing faith in each other, to cutting that thread of trust, and ultimately, to a cynical society. I believe we can course correct. But it will require a certain tuning-out of the loudest voices and a tuning-in of the quieter ones. These could be people who have earned your trust and those who have simply not lost it. Most of us are on the same team, individually striving for the collective good. I want to trust passersby freely and, likewise, I want them to trust me. Perhaps if we maintain and strengthen our communal faith in each other, it can rise to those people threatening to corrode it. Trust me. |

AuthorColin Gabler is a writer at heart. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed