For some of the world. More specifically, for rich parts of the world. At this point, most of us have used some algorithm to calculate our place in the vaccination line. There is a general consensus on who should receive it first, and even a viral campaign to change the NYTimes Person of the Year from Joe Biden and Kamala Harris to front line health care workers. Nursing homes and health care professionals is a logical next tier. Then the debate begins as to the pecking order. Fast food and factory workers? Grocery store employees? Child care providers? Teachers? Eventually we have the ‘Zoom Class’, folks who can do their jobs virtually. (There is no virtual cheeseburger). While not easy (e.g., childcare), these people have the ability to maintain physical distancing procedures not possible for other workers. For instance, an accountant can keep working from home, making sure the Kroger employees receive get the vaccine first.

This is decidedly not a post about the pecking order in the United States. This is a post about the ethics of the global distribution of the vaccine. As a shock to nobody, the wealthiest nations are securing a disproportionate number of vaccines for their citizens compared to the poorer ones. In fact, while some countries have preordered more than their total population (USA, EU, Japan, Hong Kong, Israel) 2x their population (Australia, Chile, UK), or even 4x their population (Canada), lower income countries are grasping at the remaining syringes on the shelves, hoping the get enough for those frontline workers, elderly, and health care providers mentioned above. Which raises the question: should a Zoom Class worker in Canada receive a vaccine before a factory worker in Bangladesh? To help answer questions of equality and wealth disparity, I find John Rawls’ Theory of Justice helpful. The theory has received criticism and is much more complex than this, but essentially, Rawls argues that your lot in life is pure chance. We have no say into what circumstance we are born: wealth or poverty, high or low social status, we cannot control our gender or race, our physical strength or appearance, our intelligence or sexual orientation. Rawls calls this the original position, and from this vantage point, we view the world through a veil of ignorance. If you were ignorant to your position in the world, how would you wish wealth and prosperity to be distributed? How would you want policy decisions to be made? How would you develop global principles of justice? According to the theory, if every human subscribed to this logic, the most rational arrangement would be to distribute wealth in a way that maximizes the prospects for those least well-off in society. It’s as if life is a five-card Poker draw with a huge pot in the middle. You could be dealt a Royal Flush, a 2-3-4-8-9 off-suit, or anything in between. If nobody is allowed to see their cards, would you place a bet? Or would you ask to split the pot? Of course, the problem with this analogy is that we have all seen our cards. We know what we’ve been dealt, so no justice decisions can be made objectively. In my sustainability class, I pose it this way. Imagine you were born tomorrow and fell into one of three categories: there was a 10% chance you would be advantaged (wealthy parents, high social status, smart, good-looking), a 50% chance you would be Average (middle-class parents, moderate social status, average looks and intelligence), and a 40% chance you would be Disadvantaged (impoverished parents, low social status, unattractive, low intelligence). Given those odds, how would you want the world to work?

Most students choose option B or C (even though humans tend to overvalue low odds). This is an acknowledgement that the current system is flawed, perhaps unjust. Had you peeked at your cards and saw you were holding a Full House, maybe you are just fine with inequality because you are likely to win the pot. But behind a veil of ignorance, the safe—and smart—bet is to make sure everyone gets enough, including yourself. It is a tricky conversation, particularly when you add things like gender, race, or sexual orientation. Because it does not mean that any one person is better than anyone else. In fact, that is the point. Each person has the same intrinsic value; however, certainly some folks are better ‘off’ than others. White people enjoy benefits that Black people do not just as men experience privilege simply by their gender. Even things as arbitrary as height influence how individuals fair in life. This is not to say hard work doesn’t count, but there are unseen headwinds and tailwinds at play. Applied to the COVID-19 vaccine, in the simplest terms, if you were born into a poor country you will probably wait longer for a vaccine than had you been born in a rich country. Is this fair? Did Person A choose to be born in El Salvador while Person B chose Japan? At the national and state-levels, decisions are being made based on equity, as those who need the vaccine most will receive it first. But when we aggregate to the global scale, the distribution does not seem equitable or even equal. This is not an attack on capitalism or nationalism. Countries look out for their citizens, states for their states, communities for their communities, and families for their families (see every disaster movie where the protagonist doesn’t mind everyone dying as long as their kids are saved). In my heart of hearts, I am happy the US has secured so many vaccines. By chance, my spot in line is ahead of someone born in Kazakhstan. There is no veil of ignorance. We all have a clear view of our position in life, and it is natural to use this information in our decision-making. I am not proposing a solution; I cannot even articulate the ‘problem’. There is so much about this crisis that we don’t know, and I trust that experts and policy-makers are doing their best with the information they have. This is merely a point of view. I believe the following statements are both true: People want what’s best for them; People want what’s best for others. The difficulty arises when these two statements are at odds with one another. The former will usually win the day because it is human nature to make decisions subjectively. More than that, it is rational and logical (Darwin was onto something). But taking an objective viewpoint to distributive justice leads to morally prudent decisions, and perhaps pushes us closer to balancing an unbalanced world.

0 Comments

Of course, this positive development comes amidst a backdrop of negative ones. We eclipsed a quarter of a million deaths, hospitalizations and cases are soaring, and we seem to break our daily record every day. We have learned so much about prevention strategies (e.g., masks, the three V’s), yet the usual suspects continue to act as a stronger influence on our collective behavior than logic and judgement. We suffer from ‘pandemic fatigue’, we downplay the virus, and we ‘just want to live our lives’. Lockdowns, curfews, and mandates are back on the table, and as we move into the colder months, cases are expected to keep climbing.

But why? The finish line is in sight…if still blurry and off in the distance. It makes some sense to ‘just want to live your life’ if this pandemic might literally last your lifetime. But things are different now. We don’t have to wear a mask indefinitely. We don’t have to social distance forever. We now have a finite period of time. Which leads me to the question: can America pass the marshmallow test? We’ve all seen it before. A child sits in a room with a marshmallow in front of her. She can either eat the marshmallow now or—if she can wait 15 minutes—receive an additional marshmallow. Usually the child is left alone and cameras track each agonizing second of the internal struggle. There are volumes of research on this experiment and what it tells us about the child (one study even tracked the kids from the initial sample to see how they performed on their SATs), but in a nutshell, the study determines our capacity to delay gratification. If we assign the utility, or value, of eating one marshmallow a score of 10, then you can have either 10 units of satisfaction now or 20 units later. The key differentiating variable (apart from how much you enjoy marshmallows) is the ability to handle the temporal distance between the 10 and 20 units of value. Can we wait 15 minutes to double our value or is it not worth the effort? With Thanksgiving and Christmas arriving before the vaccine, we are presented a similar dilemma. More than ever, we all (even introverts) crave time with friends and family. These holidays represent peak companionship. We engage in our favorite traditions, we nurture our most important relationships, we create new ones, and we celebrate our communal and social bonds. For many it is the most joyous time of the year. That joy stems from togetherness—literally lots of loved ones gathered together from near and far in enclosed spaces, eating, drinking, talking, singing, shooting champagne corks off in your backyard (that one may be just my family), and general merry-making. Togetherness is what we seek more than anything, and in a cruel irony, the year we need it the most is also the year we shouldn’t. Getting together with loads of people this holiday season represents the first marshmallow. It would be immediately gratifying. Like the kids in the experiment, it is tough to not give into the temptation. The second marshmallow is getting together with friends and family post-vaccine. To me it will be sweeter, but it goes back to value assigned to our marshmallow proxies. Let’s say the value of getting together with loved ones on a normal Thanksgiving is 100, and this Thanksgiving is 200. I do believe the lack of social interaction would make the hugs warmer and the conversations richer than the average Turkey Day. However, the risk of giving COVID-19 to (or getting it from) a loved one would detract from this value. That detraction depends on the individual, but for me it is at least 200. The potential of someone I love getting sick because of me takes that value to 0. That is just the risk itself. If the person actually did get sick, that zero utility turns into disutility with a life of regret. If, instead, I wait for the vaccine before I visit family and friends, the value is more than double, it’s incalculably higher. The joy of embracing my nieces and nephews, singing karaoke or Christmas carols with friends, making merry—without spreading disease—can almost not be assigned a numeric value. I realize that the above calculations are all about probabilities, so for once, let’s use our irrational behavioral tendencies to our advantage. Prospect theory demonstrates that we irrationally overweight low probabilities. This is why we play the lottery, go to casinos, and buy insurance. There is a 37:1 (2.7%) chance of hitting your number when you spin the Roulette wheel, yet we throw a $20 chip on the board and think, “This is my lucky day.” Perhaps that is because the utility received if it is your lucky day ($700; even though the odds are 37:1, the payout is 35:1 because, well, the house always wins) outweighs the low probability. Similarly, the chance of a Coronavirus infection is low. The odds are that your Thanksgiving get-together will not be a super-spreader event creating clusters of Coronavirus outbreaks. But the disutility of infecting someone is, well, you can’t really put a price tag on it. Spreading this disease—and its ripple effects—can be catastrophic. So if we are willing to throw $20 on a 2.7% chance of a lucky spin, maybe we can adopt our Roulette logic to the Coronavirus and think, “This is my unlucky day.” This is a tough post. I realize that every Thanksgiving is somebody’s last and that every situation and circumstance is unique. For some, that first marshmallow is simply worth the risk. While the vaccine is imminent, there is no official deadline for this pandemic to end. The global sigh of relief is pending but we cannot circle a date on our calendars. But if we can wait, if we can hold off on that literal togetherness, that second marshmallow might be even sweeter than the first. Christmas in July, anyone?

Essentially, we are biased to the first piece of information we receive, placing more value on it than subsequent information. This initial data point acts as the ‘anchor’ from which all other information is weighed and judged, and ultimately it impacts the final decision. We do this all the time. Think about what you would pay for a bottle of wine, a T-shirt, a gallon of milk, etc. You have established a reference price for these products based on past experiences, and you are now anchored to them. It can be an effective decision-making tool. If a gallon of milk cost $1 or $10 you would think something is up. Retailers know this as well. When a product goes on sale, why don’t they remove the old price and just show the new one? Because they know consumers like to see “Was $20 – Now only 10!” If we are anchored to the larger price, the smaller price conveys that we are gaining more value in the exchange.

How does this apply to early voting? A recent The Daily podcast entitled “The Shadow of the 2000 Election,” talked about that infamous election was shaped by Gore conceding when the results were still in question. From thereafter, it was a Bush victory with Gore contesting the results; instead of an undecided election with both candidates calling for a recount. In the collective mind of the country—and propagated by the media—America had chosen a president, and now Gore seemed like a sore loser. This perception was shaped by Bush being anchored as the winner in the minds of US citizens. This made any efforts from Gore incredibly challenging because he was playing from behind. Our initial impression of the electoral results had been made, and it was incredibly challenging to overcome. In my sales class, we discuss the importance of first impressions. When we encounter a new person, we have somewhere between 3 and 30 seconds to make our first impression. Every interaction afterward moves our assessment from that starting point—that anchor. That is why they are so important. If you begin a job interview my mispronouncing the name of the company, you have an uphill battle to gain any sort of credibility. If on your first date, you beep from your car and s/he runs through the rain to get in, you also have set the bar quite low. In both cases, you have anchored yourself low on the continuum of ‘good employee’ or ‘good date’ and have to move from low to high. You have also created a ‘halo effect’, where the interviewer or your date will make assumptions about other aspects of your character based on that snap judgment. Imagine instead that you start the job interview by correctly pronouncing the company name and a few specific, hard-to-find facts that made you want to apply. Or if you rang the doorbell, escorted your date under an umbrella, and opened the car door. Here you dropped anchor at a much more favorable place on the continuum. The same halo effect will occur, only this time it works to your advantage. The employer may assume your preparation means you are also a critical-thinker. Your date may translate your courtesy to integrity. And given the confirmation bias (another blog), both parties may look for ways to affirm those positive [or negative] attributes to keep you close to the initial anchored perception. Back to early voting and the 2020 election. As of this writing, over 66 million early votes have been cast, which points to record levels of voter turnout. This is important because when the first projections are released, we will have our reference point for the rest of the election. We will be anchored to the initial leader, making subsequent judgments from that first impression. If you are thinking that this shouldn’t matter, you are correct. Votes are tangible, simply count them up and don’t worry about perceptions. But it very well might matter for two reasons. First, President Trump has made it clear that he is willing to do anything to throw this election into turmoil. As Petyr Baelish says in Game of Thrones, “Chaos is a ladder,” and Trump embodies this idea (e.g., his Coronavirus response). The closer the initial results, the easier to poke holes in them. absentee ballots, voter fraud (, etc. The wider the margin, the harder it becomes to challenge the results. At some point, even the most narcissistic person must come to grips with the will of the people. This first impression, then, has the ability to give momentum to either campaign. Secondly, while there is no evidence that voter fraud is even a thing, the term has somehow gained a foothold in the American vernacular (again, stemming from the 2000 election). This is important because this election will be—and to some degree, already has been—decided by courts and the legal system. Make no mistake, Trump’s best prospect at re-election is through litigation, and once again, perception matters. Trump has challenged voting by mail, drop boxes, absentee ballots; he has added restrictions to disproportionately impact minority communities; he has sued states for allowing votes to be counted after certain days; he has sued governors to stop expanded mail-in voting; he has appointed countless judges to do his work for him (e.g., a New Jersey judge decided to ‘throw away’ 50,000 ballots—which is a big deal considering Trump won 2016 by 77,000 votes). The goal of all of these actions is to reduce the number of presumed votes for Biden. Plain and simple. The best way to counteract is to be so overwhelmingly ahead, that even the courts cannot come to the rescue. In normal times, we would all sit back and think about how crazy it is that the President of the United States is actively trying to limit the ability of its citizens to vote. Somehow in 2020, that is a given, and so we have to instead think of ways to overcome this dictatorship-adjacent move. That is why early voting matters. The more we can anchor the perception of a Biden win in the minds of the citizens, the harder it will be—even using purposefully deceitful tactics—to move the anchor. Regardless of the initial results, the Trump administration will challenge the methods, the media, the poll workers, governors, state laws, ballots, even voter intentions, so we should try to make it as wide a gap as possible to overcome. The heavier the anchor, the harder it is to move.

Reflecting on this and with an impending election, another mechanism came to mind as a tool to understand irrational behavior regarding our choice in November: the sunk cost fallacy. It’s important to clarify now that while this will pertain to Joe Biden versus Donald Trump, it is not an election-specific idea. The premise is simple and particularly relevant in a system where elected leaders can serve two (or more) terms and in a society where our political identities are focal points in social dialogue. So first, what is the sunk cost fallacy? Imagine you go to the movies (I know this requires real imagination in 2020). You pay $12.50 for a ticket, settle in your seat, and the lights go down. The movie starts slow, then gets confusing, the plot is disjointed and the characters one-sided. About halfway through, you realize: this is a bad movie. Now ask yourself, would you a) walk out or b) finish the movie? If you are like most people, you would finish the movie. Why do we do this? If the movie is two hours, you could use that second hour for anything: call your mother, do some laundry, meet a friend, read a book, even start watching a good movie. One reason we ‘stick it out’ is due to the sunk cost fallacy. This is irrational behavior. You cannot ask for a reimbursement of $6.25. The entire $12.50 is gone forever and, therefore, should be irrelevant to the decision to finish the movie. The first hour is also gone and should theoretically hold no bearing on how you spend the second. However, we want to ‘get what we paid for’, and so we push on. This is a common influence on our decision-making. Consider an all-you-can-eat buffet. You pay up-front and that money has been irrevocably spent before your first bite. At that point, the rational individual wishes to maximize utility by eating a satisfying meal. However, we keep adding to our plate wanting to make the most of the sunk cost. We knowingly decide to feel worse later (food coma, indigestion, etc.) for the knowledge that we got our money’s worth now. This is common in relationships. How many of us have a friend or relative that detracts from our overall happiness, yet we continue the relationship because ‘we have been friends for twenty years’? Or the toxic friendship that you don’t quit because you’ve put in the work and don’t feel like starting over. You’ve made relationship investments that provide no returns, but rather than cut your losses, you stick it out, hoping to eventually get that ROI. This concept can be applied to all elections, but I’ll focus on this November. In 2020, our political affiliations are worn on our foreheads. This can be quite literally as wearing a bright red ‘MAGA’ hat or less literal as putting a #BlackLivesMatter sign in your yard. There is a general consensus that he will be objectively considered one of the worst presidents in U.S. history. It is reasonable, then, for 2016 Trump voters to feel cognitive dissonance, and implement logic to justify the decision. “He speaks his mind and I like that.” “I’m just happy he’s not another politician.” “He’s a good businessman” (a now debunked claim). That is what makes it possible to hold two realities in your mind simultaneously. The sunk cost fallacy enters the scenario when we have a chance to make a very similar choice: the 2020 election. The next vote could act as an extension of the dissonance created by the first vote, providing an opportunity to reconsider the choice. The options are to double down on the initial bet (Trump) or vote from a clean slate without considering the bet you made in 2016 (Trump or Biden). The key is to not think about your 2016 vote as a mistake—or to think about it at all. That only creates cognitive dissonance and has no bearing on how you vote in 2020. But the sunk cost fallacy will compound the cognitive dissonance associated with the 2016 Trump voters and lead them to vote for him again in 2020. Meaning, rather than view the upcoming vote as its own distinct decision, Trump voters may see it as a continuation of their 2016 vote. By voting for him again, it affirms that they made the right choice the first time (why else would they vote to re-elect him?). While irrational, we do this all the time. Consider when you have taken one side in a friendly debate and slowly realize that either you are wrong, you had incorrect data, or you actually agree with your opponent. Which is easier to do: change sides or continue holding your ground? I can relate. Let’s return to the movie analogy. When Star Wars: The Phantom Menace came out in theaters in 1999, I was beyond excited. I thought it was going to be the greatest movie of all time. I wore a Jedi robe to the midnight show, walked in the theater, cheered when the lights went down, and then it started. As everyone knows, it was pretty terrible (apart from Darth Maul). However, not only did I not leave the theater, I decided I would profess that I loved it anyway and, to validate the point, I would return to see it ten more times in the theater. Each time—and yes I really did go 11 times—I entrenched myself as a staunch supporter of the movie, even though I knew it was bad. And each time, I accrued 2 hours and 16 minutes more of the sunk cost of initial decision, requiring more effort to overcome my cognitive dissonance. All you have to do is replace the movie title with Donald Trump, the Jedi robe with MAGA hat, and Darth Maul with the pre-COVID Stock Market, to see how tough it can be for a 2016 Trump voter to not vote for him in 2020. I do realize that many people who voted for Trump think he is a great president and will be proud to vote for him again. I just hope that the small number of people who voted for him in 2016, but wish they hadn’t, will not let a sunk cost determine a future decision. Your choice in 2016 holds no bearing on your choice in 2020. The beauty of elections is that they are distinct. You do not have to proclaim that a previous vote you made was wrong or that you are switching sides, you simply have to vote in the current election using your best judgment. By the same token, nobody should vote for Biden purely because they voted for Hillary in 2016. Their choice should also not be a continuation bet, but instead a frank evaluation and discrete decision. Every election is a chance to wipe the slate clean and make a new determination. This one is important and needs our most rational cognitive decision-making capabilities.

As soon as you take ownership of something, you can no longer sit idly by. You need to ask yourself what happened in your classes last semester and how you can turn it around. You need to admit you cheated, face the consequences, and hopefully be better for it. You need to accept that you are sick and face the potential difficulties and challenges ahead. In some ways, life is easier if you do none of the above. You don’t have to justify anything. You don’t have to draw attention to an obvious misstep. You don’t have to change the status quo.

This trait, I believe, is related to the endowment effect, and it may shed some light into behaviors associated with the Coronavirus and #BlackLivesMatter. Essentially, we tend to place more value on something once it is in our possession—whether we’ve owned it for 20 years or 20 seconds. There are numerous experiments to demonstrate this effect, often where two groups of people are given objects of equal value and refuse to trade with one another. As soon as I receive the pen, I think it is more valuable than your mug; however, had I been given the mug to start, I would think it more valuable than your pen. Just think back to school cafeteria bartering and how you thought your Little Debbie was worth your friend’s Handi-Snack AND Fruit Roll-up combined. The endowment effect can help explain many phenomena, from why someone goes ‘all-in’ holding two-pair in a 6-handed Texas Hold ‘Em (“This hand is unbeatable!”) to why fantasy football trades are so difficult to make (“My benchwarmer is better than your starter!”) to why some sellers on Facebook Marketplace are never able to see anything (“My Grandpa’s toy train is worth more than that!”). In each case, the value assigned to the object differs depending on the point-of-view. When it is in our possession, it is worth more. The possession does not have to be literal. For instance, I may think my alma mater is going to win the NCAA tournament because I take ownership of my school, which may cloud my judgment. Another example. My best friend died of leukemia six years ago, and therefore, this disease means more to me than others. I feel attached to it and, in a sense, I take ownership of it. What does that mean? In both very different situations, I act on the attachment. I spend $20 on a bracket taking my school all the way, knowing full well that is a long shot. Or I put myself on the bone marrow registry to see if I can be a match for my friend. Behavioral economists have a name for this as well: Willingness to Pay. I was willing to pay $20 on a Cinderella team because I am personally invested in the school. I was willing to donate bone marrow for my friend. Incidentally, I have remained on the registry ever since because, in a sense, I have taken some ownership of the disease itself. How do these concepts apply to Coronavirus and #BlackLivesMatter? The simple answer is that the only way to tackle them is to embrace them. The Coronavirus is not going away until we all take ownership and are willing to pay something. For first responders and essential workers, the payment is enormous. For most of us, though, the ‘payment’ is quite small. Wear a mask, maintain physical distance, don’t go out to a crowded bar. So why do many resist this simple request? Perhaps the virus has not become meaningful to them in a real way. It still seems abstract, which warrants no personal stake in the game. “I don’t know anyone who has gotten seriously sick from this disease, therefore it doesn’t matter to me. My life is fine. Why should I care?” The reluctance is all over the media, manifesting through small turns of phrase like ‘the China Virus’. This is shorthand for: “I didn’t start this thing and therefore I am not obliged to fix it.” Less offensive but more destructive is proclaiming—as the national strategy for overcoming a pandemic—that “America is a nation of miracles.” Waiting for a miracle is a wishful, passive response which assumes zero responsibility. Both of these reverse the endowment effect, pushing blame and accountability in other directions. Leaders do not meet challenges with “I’d like to start by saying this not my fault.” For some people, #BlackLivesMatter is a slogan that is neither divisive nor unifying. It may seem like a distant, niche cultural phenomenon that does not impact them personally. They may feel they have [literally] no skin in the game—a sentiment reinforced by the current administration. While Coronavirus has been met with “It’s not my fault,” #BLM has been met with “It’s not a real problem.” The Republican National Convention spent four days trying to convince America that it is not a racist country. Why? Because if a problem exists, you have to fix it. The much easier approach is to tell ourselves: don’ feel guilty, we did nothing wrong, what’s in the past is in the past, we can sleep easy knowing this is a non-issue, we don’t have to change anything about our lives, white privilege is a hoax, see look at this handful of black speakers, how could a racist country achieve that! At least praying for a miracle admits that Coronavirus exists. Pretending racism is not a problem is a deliberate attempt to reverse the endowment effect. It allows a national shirking of responsibility for anyone who feels detached from or inconvenienced by a civil rights movement. Unfortunately, unlike Coronavirus, there is no vaccine for racism. There is no impending miracle. This is a problem that requires everyone to take ownership. So many people have paid and continue to pay with their lives, their dignity, their safety, their opportunity; surely the rest of us should be willing to pay something. It doesn’t have to be protesting or supporting civil organizations. It may be as simple as acknowledging the problem exists. It may be removing personal defense mechanisms and having an open dialogue. Considering how much has been paid by generations of people of color, this seems pretty doable.

What does each response have in common? They are, by in large, factual, rational statements. However, none actually addresses the call. Each is a deliberate attempt to shift the focus away from the issue at hand and steer the conversation toward something else. In relation to the actual problem, the argument is, at best, adjacent and, at worst, destructive.

This purposeful misdirection is a form of whataboutism, a propaganda technique often attributed to Russia during the Cold War, and it should come as no surprise that as a culture we find ourselves using this type of ‘debate’ more and more. Trump has long been the champion of the form. To be sure, humankind has engaged in whataboutism since the world’s first spat (“You left the fire go out, honey.” “Well you didn’t kill a single woolly mammoth on your hunt, dear.”). But I believe the frequency and ferocity of the current usage can be attributed to how often we hear it in the news and social media. And with our president having both of those markets cornered, we cannot escape it. Whataboutism works so well because there is a certain familiarity to it. We trained ourselves to use it from a young age. Remember, as a child, getting caught doing something (stealing a cookie, getting in a fight, not doing a chore). Think about your typical response. “What about Joe? He took two cookies!” or “Why are you punishing me? Mark started it!” or “Why doesn’t Mary have any chores!” Because we felt disproportionately punished or unfairly blamed—but not that the accusation was false—these arguments were a defense mechanism meant to deflect attention elsewhere. And that is how whataboutism works. Rather than disprove or refute the original argument, the easier route is to [sometimes literally] point at someone worse or something else. Does posting a video on Facebook of a white police officer helping a black man mean that the police is working just fine? Or could it be true that there are good police officers AND the institution could use a makeover? Whataboutism often doesn’t allow for two things to exist simultaneously in the same space. It forces you to choose between two quasi-related issues, turning a logical exchange into a mish-mash of disparate, loosely associated ideas. This form of argumentation is particularly detrimental to the Coronavirus. Often pundits and presidents ask ‘what about’ the common cold or flu. “Do we shut down the schools for the common cold!? Did we close restaurants for the flu!?” If you are a person who takes the Coronavirus seriously, these statements attempt to make YOU feel like the crazy person. The logic could be completely reversed very easily. How about: “Many actions taken to help reduce the spread of COVID-19 could be applied to cold and flu season. Let’s adopt them more broadly to keep our communities healthy.” There are a few reasons that the U.S. leadership has resorted to whataboutism so often, and the previous paragraph underscores one of them. It allows you to shirk any kind of responsibility. Once you admit that the problem exists, you cannot simply point another direction and say ‘what about’. You’ve put the magnifying glass directly over the issue and now have to take ownership. Another reason is that there is no perfect response. Every policy move involves a trade-off and Trump is a man of either/or; he works in superlatives. Things are either the best or the worst, the most or the least. There is no ‘best’ response to COVID. So rather than evaluate trade-offs and develop a good plan, he has opted to keep pointing in different directions…resulting in no plan. A third reason is that you may have to admit you were wrong. The science around this disease is not static, it is dynamic, which requires flexibility in the response. And inevitably, we will make mistakes. But imagine the breath of fresh air it would be to hear an elected official simply say: “I was wrong about this and we have made policy changes based on what we now know.” But if your heels are dug in and you refuse to accept the possibility that you could be wrong, what happens when you are wrong? You change the subject. Whataboutism is the ideal tactic for the stubborn. So how do we break a cycle of whataboutism? How about…howaboutism? ‘How about’ is the phrase used right before offering a suggestion. It is constructive rather than obstructive. Whataboutism offers no solutions, just points out other problems. Howaboutism, on the other hand, immediately acknowledges the problem, and begins down the path to an answer. Granted, this path is often long, circuitous, undefined, but it is a step down that path. It meets the problem with purpose and direction, it spurs creativity and innovation, it opens the dialogue to diverse opinions but also forces compromise. I believe it can be a unifying response to cut through the divisive rhetoric of whataboutism. When I am looking to make a change, I find it helpful to find an example in practice, and follow it. Luckily, we have millions of examples of howaboutism being used all around us. That is not an exaggeration. You have to look no further than anyone in the LGBTQ community and/or any woman who has been an advocate for #BlackLivesMatter. I saw a total of zero posts from the LGBTQ community reminding the world that June was their month and we should shift our attention to them. Similarly, I heard no woman suggest that a focus on black lives was taking away from their struggle for equal rights. On the contrary, we witnessed (and are still witnessing) solidarity and compassion, a concerted effort to work together for the common objective. To be clear, women are still mistreated and underrepresented (just look no further than AOC’s remarks in Congress). LGBTQ folks are experiencing discrimination (it took until June 15 for the Supreme Court to rule that homosexual and transgender employees couldn’t be fired based on sex). #BLM didn’t magically solve other institutional and structural problems (it also highlights challenges associated with intersectionality), but those from which the focus was shifted did not use whataboutism to bring the focus back to them. Instead, they unified their voices around the cause and address the issue at hand. Instead of saying “What about us?” the message has been “How about we focus on this group right now?” The same can be done with COVID-19. Other diseases did not take the year off. But in the same way that now is the time to fight for #BlackLivesMatter, now is also the time to fight COVID-19. Instead of pointing fingers, we should be asking the right questions: How about we re-imagine education and childcare? How about we consider both the unemployment rate and the stock market as valid economic indicators when creating relief packages? How about we use what we’ve learned about reducing the spread of COVID-19 and apply it during flu season? How about we take some of the best practices from other countries and implement them here? How about we use scientific evidence, real-time data, and informed opinions when creating public policy? Words are just words, and changing from ‘what’ to ‘how’ will not solve the problem of Coronavirus. However, just the shift in thinking could at least start us down the right path.

If you have experienced this, you understand the concept of headwind/tailwind asymmetry, a phenomenon studied by Thomas Gilovich and Shai Davidai. In a nutshell, we tend to overweight the influence of barriers to our successes and underweight the influence of bridges. Consider the winter morning when your car doesn’t start, or when your colleague gets the promotion at work, or when your classmate gets the ‘easy’ group project and you get the ‘tough’ one. These are true headwinds with real repercussions. But now consider the accompanying tailwinds: you own a car, you have a good job, you are receiving a high-quality education. While the net impact of the underlying tailwinds is stronger by magnitudes, the feelings associated with the headwinds are more salient. The bias stems from the fact that the obstacles in our life are so tangible, obvious, in-our-faces, while the benefits we enjoy blend into the scenery and the normalcy of everyday life.

This headwind/tailwind asymmetry bias can be applied to white privilege, and I believe it contributes to the difficulty some have with accepting it exists. It is rational to take credit when things go well. We like to think that personal achievements are the result of our hard work and that failures are due to factors outside of our control. I’ll be the first to admit that when I have a good teaching day it is because—in my mind—I prepped like mad, perfectly blended content and humor, and just crushed the lecture. Alternatively, when I have a bad teaching day, it is not my fault. More likely I come up with an excuse, a headwind: the room was too hot, the A/V didn’t work, last night was Green Beer Day and so the students had no energy. Each of those headwinds disproportionately influenced my assessment of the outcome. Could it be that I just had an off day? Privilege is related to gratitude, and gratitude requires accepting that you had help. No matter how much energy you put into an accomplishment, there are always underlying tailwinds that push you along the way. Gratitude does not minimize the success; it just acknowledges these tailwinds. I think it is easier to recognize white privilege as the headwinds that black people experience and white people do not. We witness things like disproportionate police brutality and higher incarceration rates, and we can take specific steps to reduce them (e.g., activism, voting, funding organizations). However, there are tailwinds that white people enjoy that black people often do not, and these tend to be less conspicuous. Things like growing up in a community with social programs or getting a job interview because our name ‘sounds white’ are tougher to observe. For instance, it’s easy to forget about the tailwinds (white skin, male gender, middle-class upbringing, access to education, etc.) that led to my opportunity to become a professor to begin with—let alone have a good or bad teaching day. This is not to say that every person does not have to overcome struggles. Regardless of color, we all run into and against headwinds. Some are systematic (e.g., gender, appearance, ethnicity) while some are individual (e.g., fill-in-the-blank of your own experiences). Similarly, we all experience systematic and individual tailwinds. The challenge for white people, I believe, is to simply accept that we are pushed forward by certain tailwinds that do not exist for people of color, and we undervalue them because of the asymmetry bias. My last post was about embracing the mistakes I will make when attempting to be anti-racist. So instead of ending with that ‘food-for-thought’, I will attempt to do something about this asymmetry. My endeavor is to try and provide that individual tailwind for someone who does not have it systematically built-in. The first step is to think about specific (often subtle) ways that being white has made my life easier. Have I walked by police officers without anxiety or fear my entire life? Have I been recommended for a position over someone else with the same credentials? Have I not been given the side-eye by clerks and cashiers? Are products always geared toward me? Is my understanding of art, music, and literature actually just white art, music, and literature? And on and on. How have those tailwinds, compounded over time, shaped my life? They have offered a steady breeze at my back, pushing me through the sporadic headwinds. What can we do about it? Once we acknowledge our tailwinds, we should not feel guilty or shameful—that does not help anyone. Instead, we can be grateful and become that tailwind for someone who needs it. One example. On TV and in the movies, successful and powerful people have always looked like me. The doctors, lawyers, CEOs, politicians—and college professors—are most often white males. How has that been a tailwind? Over time, that consistent cue subconsciously instilled confidence in me, driving me to believe I could achieve the career I wanted. College professors are white males, therefore I can—or even should—be a college professor. A black person my age would not have had that constant reminder, that representation, and would perhaps lack the same confidence. The opportunity for me is to make a concerted effort to instill that confidence in, say, one of my black students who would not otherwise have it, to provide an individualized tailwind where the systematic one does not exist. But perhaps we have the capacity to create a systematic tailwind. In the model of #BlackBirdersWeek, #BlackHikersWeek, and #BlackBotantistsWeek, let’s create #BlackProfessorsWeek, August 23-30, the first week of the fall semester for most universities. Black professors can share their stories and pictures on social media, representing and demonstrating how the profession is accessible to young black people. Equally important, it can show how the profession needs MORE people of color. White people who wish to be involved can share stories and photos of black professors who changed their lives. It’s a small start to creating the systematic tailwind that so many white people like me have enjoyed, but it is a start.

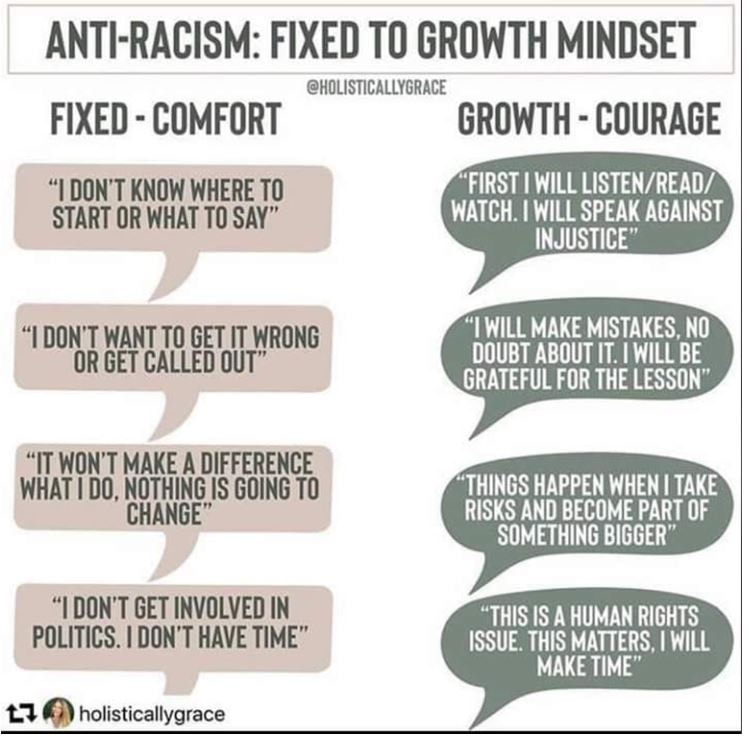

To be more vocal requires more confidence, and one way to gain confidence is to become an expert in the subject matter. If the Jeopardy! category was Star Wars, I would speak loudly and without hesitation. If the category was British royalty, I would mumble almost inaudibly or say nothing at all. In short, I do not want to say the wrong thing. I do not want to do the wrong thing. I choose to remain silent rather than embrace the possibility of making a mistake. Black Lives Matter and systemic racism are things in which I will never be an expert. After George Floyd was murdered, I have done what a lot of people have done: join a BLM protest, read, watch, and listen to as much as I could absorb, create a few social media posts, support black organizations, etc. But apart from that, my gut reaction was to just keep my head low and mouth shut. Not only am I not an expert, as arguably the most categorically privileged type of person (white, male, straight), nobody wants to hear from me about this issue.

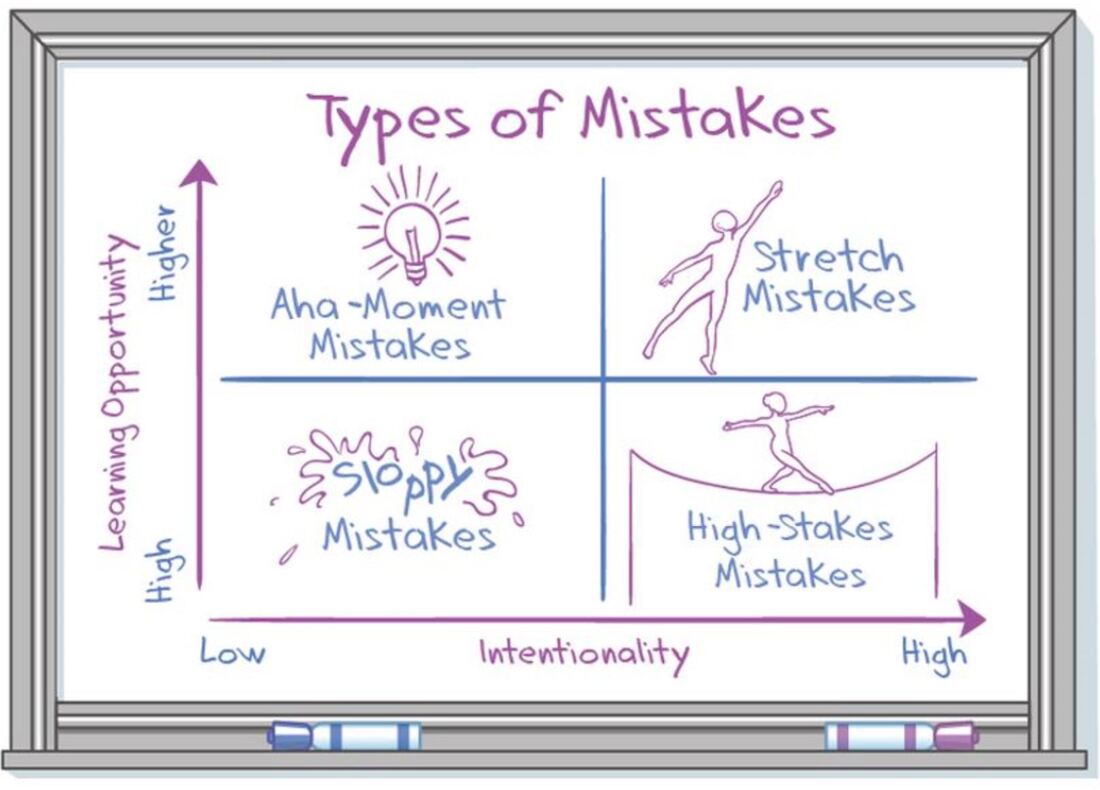

In general, we can avoid Sloppy Mistakes. If your cell phone rings in church or you forget to shut off your car’s engine overnight (guilty of both), that was sloppy, and you didn’t really learn much either. An Aha-Moment Mistake is also unintentional but provides a big learning opportunity. Perhaps your tomato plants die from over-watering or you put a red T-shirt in the white laundry (also guilty of both). You did not intend to mess up, but you’ll never make either mistake again. As a professor, my goal is to help my students not make High-Stakes Mistakes. We conduct mock interviews where the worst thing that can happen is they lose a few points. The goal is to use feedback to ensure they do not make those mistakes in the actual job interview—where the stakes are high. Better to slice your tee-shot on the driving range than at the U.S. Open. And finally, Stretch Mistakes occur when you try something new. Here you expect to mess up, but you learn from it. The first time you make a soufflé, it will probably be burnt. The first time you parallel park, you will probably hit the curb. But it is not as if you were lazy or didn’t try. It is simply a matter of taking a risk. The mistake is bound to happen and necessary to achieve growth.

So what does that mean for approaching the black lives matter movement and racism? As the most important issue in our world today, it requires voices. For me, it means not shying away from discussions because I am not confident on the subject matter. (There are not enough books/podcasts/documentaries in the world to do so). It means embracing conflict, making mistakes, and growing from them. But what are the right mistakes to make? Sloppy mistakes are the result of laziness, and this problem is too important to be lazy. Assumptions based on race, un-vetted social media posts, these should not occur. I have already made an Aha-Moment Mistake. The first time I saw a “Defund the Police” sign while marching in Athens, OH, I thought “they can’t be serious.” Forty-eight hours later, I had a completely different point of view, informed by a diverse set of opinions and statistics. I now engage in those discussions not because I am an expert but because I realize its importance. I also understand that being uninformed and silent is a privilege that many do not have. I am wading into new territory, and therefore, I am bound to make Stretch Mistakes. But rather than shy away from them, I need to embrace them. I am going to say the wrong thing. Racism is embedded in our culture that this is inevitable. I continue to eliminate phrases from my vocabulary, add new ones, and share what I have learned—and need to learn—with others. If the goal is to become a better person, an ally, an advocate, an engaged citizen, then I will mess up. I need to be grateful for the lesson in whatever form it takes. I did not forget about High-Stakes Mistakes. In theory, these should be avoided, but the stakes are intrinsically high, and there is no avoiding them. Inaction is also a privilege that many do not enjoy, and it can be just as detrimental to any cause. This means I need to embrace the conflict that may come from actions. It may mean difficult conversations with friends and family. It may mean alienating friends and family. But if the result is a just society, it is worth it. We don’t get to decide the stakes in this case. While the BLM movement is intertwined with the Coronavirus, they require different things from us. The best approach to COVID-19 for the average citizen is relatively simple: stay at home in your comfort zone, wear a mask which muffles your voice, wash your hands to be clean of the problem. The approach to ending racism, however, is more complex. It requires going out of your comfort zone, removing the figurative mask stifling your voice, and getting your hands dirty because this problem cannot be simply washed away. It will require a growth-courage mindset, and that will only occur if we are open to making mistakes.

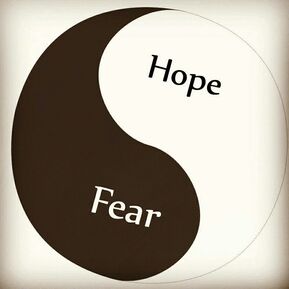

This dichotomy recalled an episode from ‘The Weeds’ podcast. Essentially, they broke down our two political parties into similar groups using one word descriptors: Democrats=hope and Republicans=fear. Thinking about the words objectively, this resonated with me because of its simplicity and—in my opinion—its accuracy. As the podcast noted, you only have to look at the last two winning presidential slogans. Barrack Obama used “Hope and Change” while Donald Trump used “Make American Great Again.” The former seemed to view the changing global landscape as something to be hopeful about. The latter seemed to suggest that things were better ‘back in the good old days’. Obama sought change while Trump longed for the status quo, or rather, what used to be the status quo.

Both men were looking at a similar situation: the unknown. Where is the United States heading? What is our American identity? How should we handle issues such as immigration, systemic racism, economic issues, foreign affairs, inequality, human rights, etc.? They just viewed the situation through different lenses. You could argue (as pundits do) which is the correct lens, but the important thing is that the same basic picture can be framed so dramatically differently. Most people identify with both hope and fear in some way. How do you answer the question: what does the future look like? Is your answer “Things will get better,” “Things were better before,” or somewhere in the middle. You could call these liberal or conservative values, but both can be useful—now more than ever. To borrow the cliché, in the midst of this pandemic, we need to work across the ideological aisle as we think about next steps. We need to balance a sense of hope and fear. Fear can be a good thing. We are familiar with the fight-or-flight response to a dangerous situation. Scholars suggest this phenomenon evolved from our time on the plains thousands of years ago. Sensing a predator in the high grass, we quickly determined it was time to retreat to safety. This instinct evolved to ensure our survival. Today, we are fearful of an invisible virus that spreads easily and indiscriminately while harming and killing discriminately. This fear also evolved to ensure survival. If we did not fear the Coronavirus, we would fall victim just as we would have to a lion on the savanna. Fear can be a bad thing. However our fear manifests (anxiety, stress, doubt, suspicion, despair) it acts as a self-imposed limitation on our potential. We can become paralyzed by it and miss opportunities. Often a difficult or threatening situation reveals our most admirable qualities, from standing up to a bully to speaking in front of a group. Overcoming fear shows courage and resolve. Fear is omnipresent right now, and while it is certainly helpful, succumbing to it hinders our resilience. Hope can be a good thing (the character, Red, from The Shawshank Redemption would argue “maybe the best of things”). Without hope, the future is bleak, but hope is more than optimism. The optimist wants to believe the future will be good. The hopefulist (patent pending) actually expects it. We hope that the spread will slow, we hope that therapies, drugs, and vaccines will come to market quickly, we hope for the restoration of ‘the new normal’. This provides us with a sense of purpose to continue in our day-to-day lives, to pursue goals, and put things on the calendar. Hope can be a bad thing. Like fear, hope can lead to inaction if we feel as if the hard part is already done. Hope without action is not a strategy, it is wishful thinking. Hoping that your dog will sit, stay, and roll over will not lead to a well-behaved pet. It requires training. Hoping that someone will ‘figure out’ climate change will not reduce global temperatures. It requires massive coordinated effort. Hope provides the direction, but action gets you to the destination. Expectations can indeed be great—if you do something to make them happen. As countries, states, counties, and cities unveil their new guidelines and phases of reopening, our society faces a major test, and like a final exam in school, both fear and hope can be beneficial if used appropriately. If you are paralyzed by a fear of failing, you probably will, and if you are purely hopeful that you will earn an A, you will probably not. Hope and fear are static; they require action to be useful. If your fear motivates you to talk to your teacher and your hope motivates you to study harder, you will succeed. Perhaps hope and fear are two sides of the same coin. If so, there is value to be gained from both heads or tails if a healthy balance can be achieved. We can use our fear to take precautions and safety measures, to avoid unnecessary risks, and save each other’s lives. But we can’t allow it to make us feel helpless. Similarly, we cannot hope the virus away, but we can leverage our hope to maintain positivity, to offer encouragement to those who need it, and to help our communities recover for a future we expect. We have the ability to activate the positive motivations from both hope and fear, which can give us control over the situation. Because in some ways, ‘things were better before’ but ‘things will get better’.

Sometimes this trust is earned. Consider your friend who has built it over decades or the medical expert through education and practice. But in the case of driving down the highway, we give it without a second thought. This implicit trust is a good thing. It is what makes our society so livable. We make assumptions that our fellow man and woman will take the ethical high ground. And with rare exceptions, this trust is warranted and reciprocated. Imagine a world where it didn’t exist, a lifetime filled with anxious moments wondering if someone was holding up their end of this unspoken agreement.

This baked-in trust is fundamental to a benevolent civilization, but in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic—when you could argue it is most needed—I feel as if it is in jeopardy. Consider any news program, social media post, or press release. Do you trust the reporting and the statistics? Do you trust the data and its interpretation? Do you trust the person providing the information? If you answered No, that is probably a good thing. For instance, if you trusted President Trump in February, you thought the virus would be miraculously gone by now and we’d have a vaccine, if you trusted him in March, you thought the flu was worse than the Coronavirus and everyone would be tested by now, and if you trusted him in April, you might have literally drunk bleach. If you trusted Beijing’s initial reports, you’d believe Coronavirus killed far fewer people than it actually did in Wuhan. If you trusted the Bakersfield doctors, you would have too much mis-extrapolated information to even process. If you trusted certain memes, you’d believe that dolphins are swimming in the Venetian canals. In some cases, finding out that we shouldn’t have trusted the source is fairly benign and non-consequential (if you want to daydream about dolphins squeaking while jumping over the Rialto Bridge, what harm is there in that?). But the others are breeches of our trust with the potential for catastrophic consequences. Trust is wholly dependent on truth, and like so many virtues, it can take a lifetime to build and seconds to evaporate. Truth, likewise, depends on trust. We tend to only speak our deepest truths to our most trusted friends or proven experts. But we also trust, more generally, that we, as humans, are all playing for the same team. We default toward trusting that we will individually take the high road for the collective good. Part of what keeps our societal fabric so tight is the thread of freely-given trust woven throughout it. And that is why our cultural trust is in jeopardy. When we cannot trust that public officials, medical experts, the media, and the President of the United States, are playing for the same team, who do we turn to for leadership? Now is not the time for our basic trust in each other to erode. Over the coming months, treatments and vaccines are going to be available. We need to trust public health officials to make the ethically appropriate decision on distribution measures. Incidentally, there is no ‘right’ way to do so. One could argue first-come-first-serve, life years, quality of life, best chance of survival, instrumental societal value, among others. The key here is that we trust medical ethicists to make the best decision given the set of parameters. Further, there are many more viruses like this that could strike down the road. We need to trust that our government will fund the studies to get ahead of the next crisis. We need to trust that when our governor issues another month of social distancing, he or she has our interests in mind and is not motivated by political reasons. We are going to have to trust that our education system is actively looking for creative way to engage students. On a personal level, one day we are going to go to a pub to meet friends. Like passing drivers on the highway, we will have to trust that everyone has taken proper precautions or they wouldn’t be there. Skepticism is not inherently bad. Skepticism can further discussion, spur debate, and lead to an optimal course of action. Cynicism, on the other hand, offers little value. It halts discussion, ends debates before they start, and leads to self-interested action. However, it is becoming more prominent with every news cycle. While conspiracy theories, fact-massaging, convenience sampling, and ulterior motives are nothing new to 2020 or COVID-19, they have been accentuated by the current imperative for information. This makes us more vulnerable to losing faith in each other, to cutting that thread of trust, and ultimately, to a cynical society. I believe we can course correct. But it will require a certain tuning-out of the loudest voices and a tuning-in of the quieter ones. These could be people who have earned your trust and those who have simply not lost it. Most of us are on the same team, individually striving for the collective good. I want to trust passersby freely and, likewise, I want them to trust me. Perhaps if we maintain and strengthen our communal faith in each other, it can rise to those people threatening to corrode it. Trust me. |

AuthorColin Gabler is a writer at heart. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed